This article is the third in a series of four articles that highlight (and “hack”) the American Council on the Teaching Foreign Languages’ (ACTFL) six core practices in the context of actual classrooms. These Core Practice Hacks are meant to guide both planning and instruction. In each will be ideas, examples and reflection points for us, as teachers, to get R.E.A.L. about what’s going on in our classrooms. R.E.A.L. stands for the process of reflect, energize, assess and lead.

Read the series:

Meredith White

As teachers, we can talk about pedagogy until we’re blue in the face. At the end of the day, however, we want strategies and resources that fit our classrooms and personalities, so we need choices.

Furthermore, said choices need to be the best option for our students, not with only ourselves as teachers in mind. If our classroom is truly to be student-centered and student-led, we need to give them voice and choice. In the context of the first three core practices, both voice and choice are key with focus on the planning and the intention.

Someone else’s classroom may not fit our experience level, personality, department chemistry and most importantly, student needs. It is for that reason that I generally replace the term “best practices” with “highlight reel.” These are the games, templates, websites, ideas and resources that are the educational triple threat: we use them comfortably, we enjoy them and they work.

When it comes to the E in R.E.A.L. – energize – nothing is more energizing than finding a new resource that streamlines a process, makes something easier or engages students in a different and meaningful way. Below, categorized by Core Practice, are some key components of my classroom that help my students and me be successful. There are a mix of technology, strategies and professional resources that are appropriate and editable for all levels and languages.

Core Practice: Using the target language as the vehicle and content of the learning

For many educators, speaking in the target language 90 percent of the classroom time can be overwhelming, and for everyone it is an ongoing challenge. So, how do we stay in the target language, maintain comprehensibility, personalize input and meet our objectives?

To that end, it is perhaps less daunting to focus on the 10 percent of the time spoken in English rather than the 90 percent of the time that is not. Being very selective about the English spoken in class and then defaulting to the target language for the rest can make planning easier.

For example, some teachers clarify objectives or instructions in English (when it is needed) and default to the target language for the rest. Other teachers may choose to use English for reflections or cultural comparisons that are complex. I teach novices (levels one and two) on a block schedule with 90-minute periods, so that gives me nine minutes a day for English, and I find it easier to plan for the nine minutes than the 81 of Spanish. I share this information, as well as my thoughts about it, with students. They don’t feel ambushed, lost or trapped when they can look up at the board and see how intentionally I have planned my use of English and that it’s for their benefit.

For me, though, this is not enough. I also have a few students whose classroom job is to make sure I’m comprehensible (try using three students: one struggling, one on-target and one exceeding). When I’m not comprehensible, they let me know (this can be a simple head shake, fist-to-five gesture, hand raise and, “We don’t understand” in the target language). I then slow down, rephrase and go from there. This helps foster classroom community because the teacher is not using the target language at them or even worse, against them, which makes the language something they resent and eventually dislike.

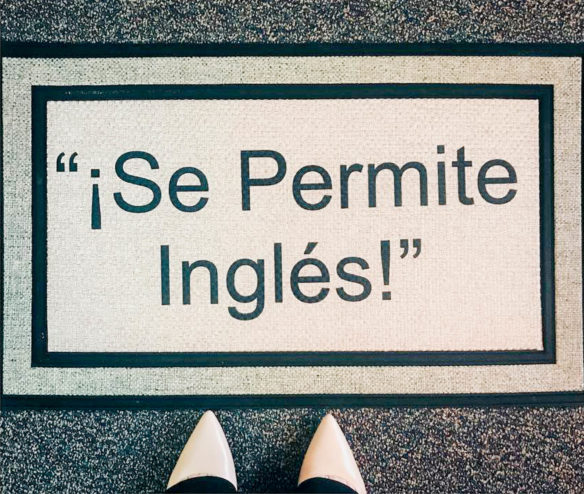

Meredith White, a high school Spanish teacher in Georgia, uses a doormat that says “English is permitted!” in Spanish to remind herself to stay comprehensible while speaking in the target language 90 percent of the time. If she realizes her students are not understanding her, she asks them, in Spanish, if English is permitted while pointing to the mat. This is one tool White uses to make speaking in the target language feel enjoyable for her students, not like a constant test.

Submitted photo by Meredith White

Students, though, are sometimes absent or simply forget to remind me of being comprehensible. To remind myself, I have created my own system that consists of a doormat that says “English is permitted!” in Spanish. At the beginning of the year especially, it can be a great class question in the target language when I realize I’m not being comprehended. “Class, is English permitted?” I say it in Spanish and point toward the mat. They usually nod their heads enthusiastically, relieved, and I quickly clarify while staying in the target language. Again, the message is that the target language is not a trap, it’s supposed to be enjoyable and understandable, especially in the novice levels.

Lastly, when it comes to exposing my students to authentic resources, real-time Spanish and more, my go-to is our class Snapchat account. Read all about that on this Google doc.

Core practice: Fostering interpersonal communication

With classes of more than 30 students, it can be really hard to build in opportunities for students to speak in the target language interpersonally and meaningfully. Novices, especially, can have a hard time seeing the value in speaking with a classmate, yet get nervous when speaking with the teacher. I’ve found over the years, though, a couple of hacks to vary the conversations and get repetition without being repetitive.

I reserve our computer lab or a laptop cart (with front cameras) weekly or bi-weekly. The front cameras let students record and see themselves as they speak in the target language. Students work on various assignments I give them, as well as a specific assignment for that day. During that time, I pull students aside to chat with me for a quick assessment of their interpersonal communication skills. This is great one-on-one time, and I’m not worried about what the other 35 are doing.

For a delayed interpersonal conversation, www.flipgrid.com is an invaluable tool. Students record themselves responding to a prompt you’ve given and then they can respond to each other. It’s interpersonal in a way that isn’t embarrassing or threatening and students can have some notes prepared so they don’t feel ambushed. Moreover, you as the teacher can record and send back your feedback, too. Flipgrid is a lifesaver and by far my favorite site.

Georgia Spanish teacher Meredith White uses a well-known tabletop game to help her students learn to speak the language more. Before drawing a game piece, the students must answer a question or make a statement that corresponds to the color of the piece they wish take out of the stack.

Submitted photo by Meredith White

When it comes to in-class interpersonal communication with classmates, I like to use games that they’re likely already familiar with. Jenga is a great game (noise, suspense, action) and easy to work into the classroom. I use a Jenga block set that has six colors, and all I have to do is design questions for each color. Before students can pull a block, they have to answer the question or make a statement according to the color of the block they want to pull.

Ultimately, interpersonal conversations require effective questioning in any content area. It is therefore critical to know how the instructional practice of question sequencing works, especially in literacy courses like world languages. Learning about this instructional practice and then incorporating it into lessons changed my entire perspective on interpersonal communication. My tasks immediately became more relevant and sustainable because they were no longer scripted out and predictable for Partner A and Partner B.

Core practice: Backward design of world language curriculum

When it comes to curriculum design, most of us don’t have much say. We’re handed a textbook or some kind of central resource and told that students “must know X by May,” ready, set, go. Couple that with vague teacher preparation and the result is people who are jaded by lesson plans, objectives, and end up merely filling 47 minutes.

When we learn how exactly to craft a relevant objective in a world language class, this all becomes much easier. For example, saying “students will be able to understand the difference between preterite and imperfect” is not an effective objective. Rather, saying “students will be able to express childhood memories using multiple time frames” is more concrete and definitely more interesting.

We must think what the students are going to do with the language, not merely which parts of the language they’ll use or what they’ll know about the language. Driving tests measure how well students drive, not how much they know about cars; language works the same way.

When I needed to get better at this, I discovered about Integrated Performance Assessments. I also started giving students the study guide and tasks at the beginning of the unit to be transparent about what our goal was. Instead of thinking in terms of what my students needed to learn, I began to ask myself, “What is the functional skill that my students need to be able to do and why does it matter?”

A family tree poster at the end of the unit on family was a waste of my time and the only reason I was using it was because it was easy and I already had the rubric. Why weren’t we tackling the bigger questions of family, such as relationships and the cultural implications of shared spaces and lives? These topics definitely can be scaffolded for appropriate support and expression. Our students are novice language users, not novice thinkers.

As my pedagogy shifted, I also was exposed to more examples of what people in other places were doing successfully – interviews like this one with Greta Lundgaard became a go-to resource to reinforce the changes I was making and paradigms that I really needed to evolve.

Next in the final installment of this series I’ll share other ideas and resources based upon the last three Core Practices from the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages:

- Core practice: Teach grammar as a concept and use it in context;

- Core practice: Using authentic texts and resources; and

- Core practice: Provide feedback to improve learner performance.

Meredith White teaches Spanish at Peachtree Ridge High School (Gwinnett County Public Schools), in Suwanee, Ga. She is on the Executive Board of the Southern Conference On Language Teaching (SCOLT), and she serves as its program co-director and social media coordinator. In addition, she is a doctoral student, #Langchat moderator, and Path2Proficiency blogger.

Excellent article! First, I found it interesting how you shift the focus onto the 10% of instruction that is in English, as opposed to the 90% that is in the target language. Also, I love your idea for having 3 students to let you know if you are comprehensible. As teachers, sometimes it can be difficult to tell if we are comprehensible or not. Also, I love the idea of using Jenga in the World Language class. I can definitely see myself stealing this idea for my French class! You might be interested in my blog: teachinginthetargetlanguage.com. One of the topics I focus on is keeping 90% of instruction in the TL. Also, I often post about incorporating games into our everyday instruction. I definitely would not have thought to use Jenga until now! Thank you for sharing your ideas. I am looking forward to reading more of your posts! :)

Thanks, Laura! Yes, I’ve been to your blog many times and follow you on Twitter! Yay, for the Twittersphere! :) (I’m @PRHSspanish!)