Alex Chadwell

Arts in education, arts-based learning, arts integration, STEAM, whatever you want to call it, has decades of evidence-based research and thousands of years of lived experience to show how teaching and learning in, with, and through the arts is a uniquely potent method of education. The inclusion and promotion of arts in education is so powerful because all education exists in a sociocultural context.

More specifically, education is a sociocultural practice. Merryl Goldberg, sums it up in her book, “Arts Integration: Teaching Subject Matter through the Arts in Multicultural Settings.”

“The arts are fundamental to education because they are fundamental to human knowledge and culture, expression, and communication,” she said.

While the notion of arts as an essential aspect of the human condition is generally supported by society at large, the arts in American schooling have been relegated to the fringes. Often, the arts in schools are isolated both in terms of curriculum and their physical location within the school building. This sequestration has also led to the false dichotomy of “arts for art’s sake” or “arts for academics’ sake.” One of the reasons for this separation is the belief that aesthetic ways of knowing are not as useful or “cognitive” because they are too emotional and abstract. Yet, it is within this emotional-cognitive binary that aesthetic ways of knowing excel and transcend. Over the past few decades, as the understanding of the human brain has deepened, there has been a paradigmatic shift from understanding humans as thinking bodies that feel to feeling bodies that think. While there has certainly been more emphasis on socio-emotional learning over the last two decades, much of the education in America is still predicated on the belief that learning is unemotional, disembodied, and individual. Viewing art as an epistemology offers an alternative.

First grade teacher, Karen Gallas, writes of this perspective, “What we understood from our experiences with the arts as subject matter and as inspiration was that knowing wasn’t just telling something back as we had received it. Knowing meant transformation and change, and a gradual awareness of what we had learned. For both children and teacher, the arts offer opportunities for reflection upon content and the process of learning, and they foster a deeper level of communication about what knowledge is and who is truly in control of the learning process”

To further explore this idea of arts as epistemology, I’d like to present an activity that I developed for the Lexington Philharmonic (LexPhil). It’s called the MusicLab. One of the crowd-favorites of the MusicLab is a synthesizer of sorts. Using a Makey Makey, one can turn an arrangement of any conductive objects into a keyboard. I first encountered this technology in a video of the composer and teaching artist, Angélica Negrón, composing music with plants and electronics. I realized right away that I could integrate something like this into the programs I was developing at LexPhil. One of my primary goals is to create and facilitate spaces and activities where people of all ages and abilities can immediately and meaningfully engage in the creative process. The pervasive myth that prior to any meaningful art being created, one must endure years of advanced technical study is a harmful one, and one that has sanctified “creativity” as a characteristic only few possess.

There is an element of wonder and curiosity that engaging with a potato/lemon/lime/banana keyboard engenders that pushes students to know beyond their existing cognitive schemas. Through a tactile and aesthetic experience, the concepts of “conductivity” and “circuitry” are embodied as electricity travels through the body. Simultaneously, this knowledge is transformed and communicated through the creative act of making music. Engaging aesthetically is a distinctive way of knowing. My colleague and fellow teaching artist, Katie Rainey, writes, “I think about how much arts education has allowed me to identify how I know things while making space for how others know things. And how important it is to see that pathway of thinking.”

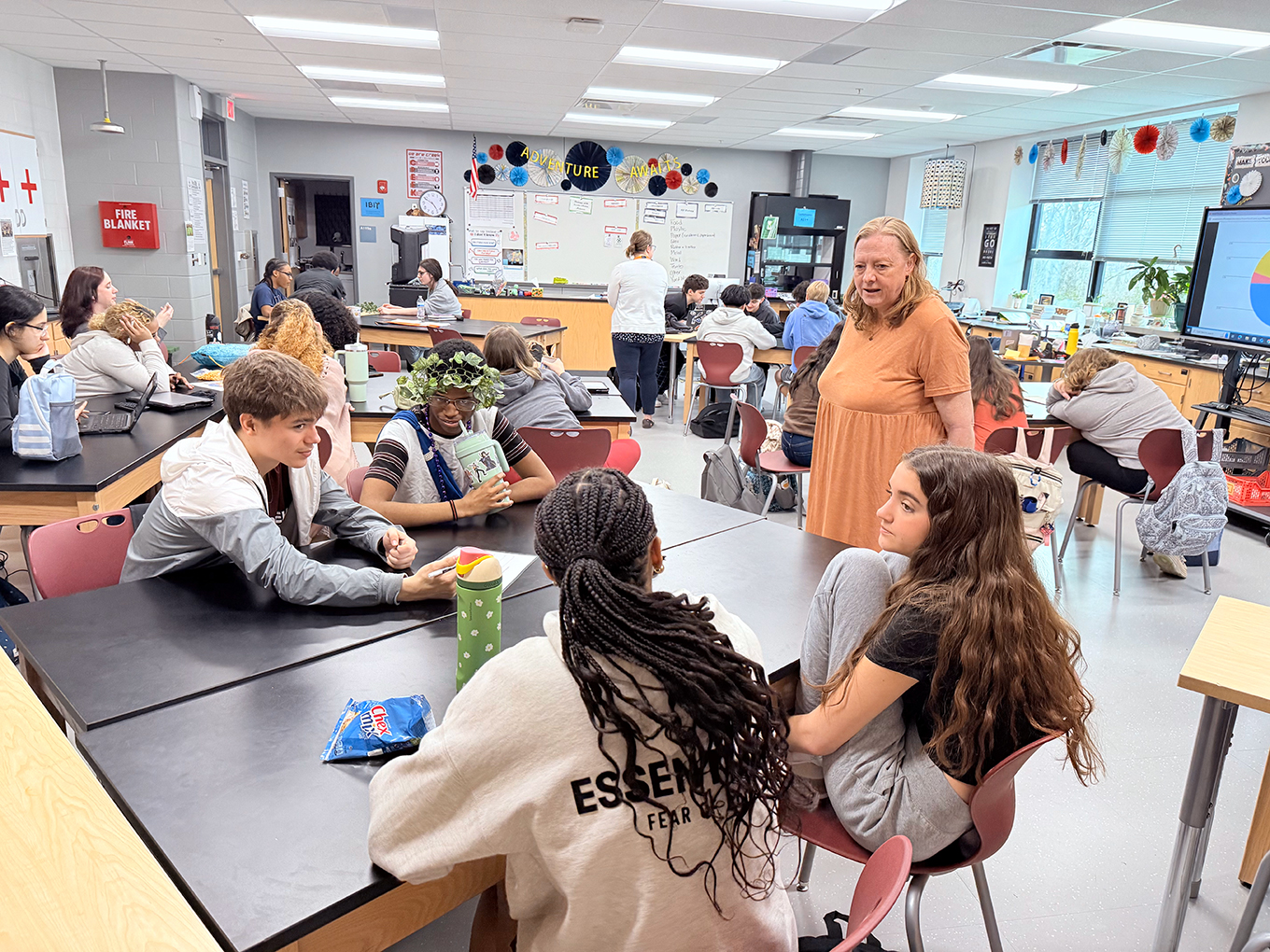

The conversation around lack of arts in schools is typically seen as an issue of deficiency and this is certainly the case regarding material resources. Public schools and non-profit arts organizations and cultural institutions are chronically and severely underfunded. The arts are almost always the first thing to be cut. However, through an asset-based lens, even in marginalized and under-supported schools, aesthetic means of knowing, communicating, and expressing are present; from the music coming out of students’ earbuds to the visuals used in presentations, to the movement within every classroom, to the conversations in the hallways. Whether we embrace it or not, arts and culture are one of the primary methods humans use to make sense of and meaning in their lives. Teachers can, through a lens of culturally sustaining pedagogy, promote and strengthen these existing aesthetic means of knowing.

In a world that increasingly requires the development of students’ emotional literacy, social imagination, critical consciousness, and cultural competence, I encourage us as educators to find ways to include aesthetic ways of knowing and being in the classroom. Through multiple modalities, arts-based learning provides students with self-transcendent experiences that foster the ability to see their existing reality in new ways and to imagine new worlds.

Alex Chadwell is learning and partnership programs manager for the Lexington Philharmonic and LexPhil MusicLab.

References

Alim, H. S., & Paris, D. (eds.) (2017). Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies: Teaching and Learning for Justice in a Changing World. Teachers College Press, Columbia University.

Frasca, J., & Kerr, I. (2023). Innovating Emergent Futures: The Innovation Design Approach for Change and Worldmaking. Emergent Futures Lab Press.

Gallas, K. (1991). Arts as Epistemology: Enabling Children to Know What They Know. Harvard Educational Review, 61(1), 50.

Goldberg, M. (2021). Arts Integration: Teaching Subject Matter through the Arts in Multicultural Settings (6th ed). Routledge.

Hanson, M. (2023) U.S. Public Education Spending Statistics. EducationData.org. https://educationdata.org/public-education-spending-statistics

Maggs, D., & Robinson, J. (2020). Sustainability in an Imaginary World: Art and the Question of Agency. Routledge.

Magsamen, S., & Ross, I. (2023). Your Brain on Art: How the Arts Transform Us. Random House.

Peppler, K., Dahn, M., & Ito, M. (2023). The Connected Arts Learning Framework: An expanded view of the purposes and possibilities for arts learning. The Wallace Foundation.

Rainey, K. (2023). VALUING WAYS OF KNOWING: An Artist Goes to Law School. Creative Generation. https://www.creative-generation.org/blogs/valuing-ways-of-knowing-an-artist-goes-to-law-school

National Assembly of State Arts Agencies. (2023) State Arts Agency Revenues Fiscal Year 2023. National Assembly of State Arts Agencies.

Leave A Comment