Andrew Waterhouse

All educators have heard these classic phrases sometime in their tenure: “I don’t have time for that” or “I need to focus on the test.” These phrases often are heard from teachers who teach Advanced Placement (AP), end-of-course and/or college/career preparatory courses.

Having taught AP, I can relate. I simply wanted students to feel prepared for the College Board exam at the end of the year. There is so much content in the curriculum, it’s difficult to get through it all.

I did what I thought was best: rounds of review, hours and hours of homework, and packet-driven work. Learning was rooted in direct instruction, practice problems and memorization. Of course there were engaging labs and activities the students enjoyed, but the overall goal was to get each student ready to pass the exam.

Most of my students were compliant and on task, but they weren’t authentically engaged or driven to learn the content. The passion was lacking. I knew they wanted more.

If you haven’t noticed, the “more” is back in full swing with project-based learning (PBL). PBL is student-centered, active learning through authentic projects. Projects are often 4-8 weeks long and are the vehicle for learning. Students are tasked with answering a real-world question and presenting their solutions.

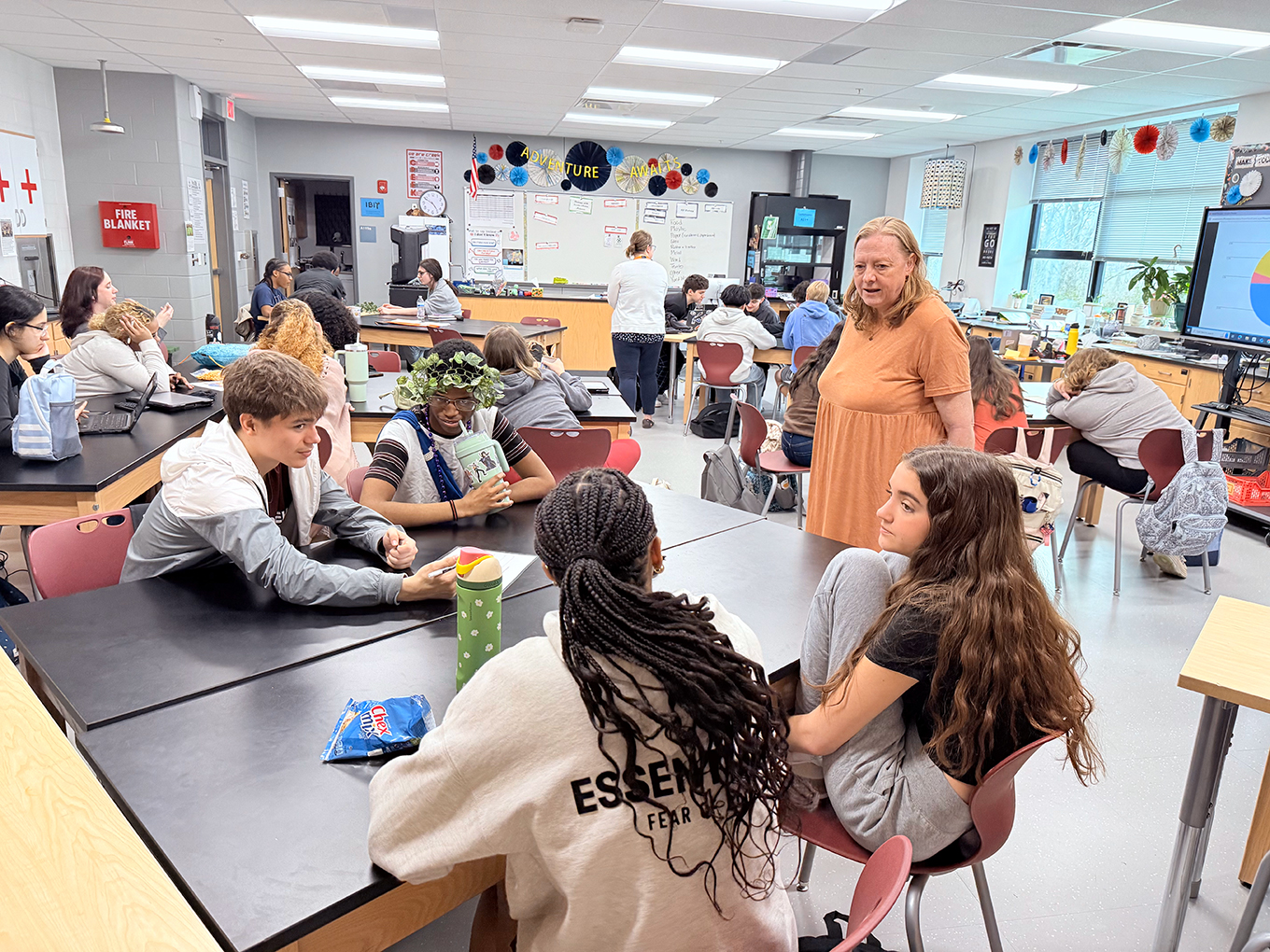

While PBL helps students get more engaged with their learning, it’s often not used in AP classes. AP teachers worry the projects won’t focus on topics that are pertinent to the exam. This year at Ballard High School (Jefferson County), I wanted students to have a deep knowledge of the content and an authentic learning experience – all while preparing them for the exam and life after high school.

So, how did I do it?

- Deconstructing standards and planning

I first deconstructed the AP standards into smaller, more specific concepts (learning targets). Then, I began to connect these concepts to relevant, real-world applications. For example, energy resources and consumption is one of the seven topics in AP Environmental Science. The topic focuses on nonrenewable and renewable energy sources.

I took these two concepts and created an Energy proposal project. Students were part of an energy planning firm and were tasked with developing a 10- to 20-year energy plan for a nearby town. They had to research energy trends in the area, analyze the environmental impact of the current energy sources, calculate the cost of implementing new energy sources and create a timeframe for completion. Check out some exemplars to see the authentic work.

Key takeaway: I didn’t lose time trying to teach them these concepts and then assigning an end-of-unit project. Instead, they learned about the key concepts as they worked on the project.

- Mini PBL projects

After deconstructing the standards, I started to plan out a few mini projects throughout the year. I initially thought about a project for each unit, but I wanted to be more realistic. So I planned about two or three mini projects each semester.

Each project had to:

- Be 2-4 weeks long

- Be standards based

- Have some real-world context

- Be multi-disciplinary

- Ask students to create or construct something

Another example was a life-cycle-analysis digital poster students created for the pollution/human waste unit. Students had to construct a life-cycle-analysis of a manufactured good and illustrate the cradle-to-grave process. I wanted them to illustrate a deep understanding of the process.

- Long-term PBL projects

I also planned one long-term project each semester that incorporated some of the essential skills of the course. Students chose one project from a menu of options and worked on it throughout the semester. They presented their findings to the class and reflected on their experience. Some examples of long-term projects included: creating a schoolwide environmental club and sustaining it, teaching lessons on recycling and sustainability to elementary students, and creating a YouTube channel full of “how-to” episodes dedicated to sustainable practices.

Yes, I still gave multiple choice and free response assessments in addition to their projects to help prepare them for the exam. But, I gave shorter versions (15-20 multiple-choice and one or two free response questions) that were still AP style. Typically, AP chapter or unit tests are 30-45 questions. Therefore, as students were showcasing their learning authentically through projects, they still were preparing for the exam.

At the beginning of the year, students were complaining that I “wasn’t teaching them.” It was difficult for them to realize how much learning they were doing as they worked on the first project. But by the second and third mini project, they were actively engaged in the process. Some were truly ecstatic when I would announce another project.

At the end of the year, I gave them a choice for their final exam. They could take another multiple choice assessment or they could create a product demonstrating their knowledge of the standards. Every student ended up choosing the product.

The true goal here is the learning; learning needs to be active, experiential, relevant and deep. It is more than possible to integrate PBL into an AP curriculum while putting students in a position to do well on the exam.

Hopefully my experience is encouraging. Don’t feel pressured to stick to the rigid curriculum! Make sure you give yourself time to properly plan and let the rich, authentic experiences unfold.

Andrew Waterhouse has taught science for six years in Jefferson County schools, four at Doss High School under the leadership of Marty Pollio, and two at Ballard High School. He is a doctoral student at the University of Kentucky studying educational leadership, a district ambassador, a Classroom Teachers Enacting Positive Solutions (CTEPS) fellow and a JCPS Forward leader.

Leave A Comment