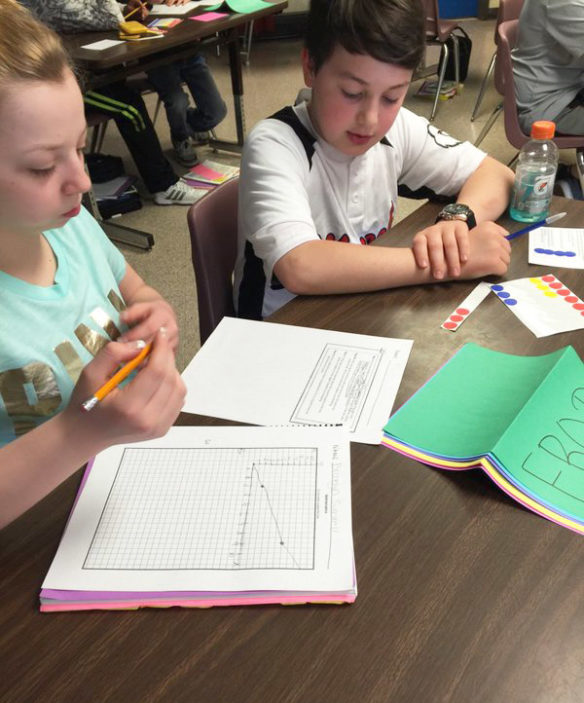

Brooklyn Sumrell, left, and Logan Kuhn from Amber Richardson’s 7th-grade math class review their own data from a district assessment at Meyzeek Middle School (Jefferson County). Richardson and Jennifer Cox, the school’s goal clarity coach, taught a mini lesson on how to give and receive constructive feedback. Students were able to talk through thinking with a partner around missed concepts, annotate and ask questions for understanding, then make corrections.

Photo submitted by Jennifer Cox

By Jennifer Cox

jennifer.cox2@jefferson.kyschools.us

Entering Amber Richardson’s 7th-grade mathematics classroom at Meyzeek Middle School (Jefferson County), one might think something out of the ordinary was occurring. This did not sound like a typical middle school mathematics class. Yet taking time to listen, I could hear the learning.

“Let’s try to find another proportion to prove our answer.”

“Why don’t we try to set up the problem and find out if our guess is correct?”

“What do we know if the point we plot falls outside the line?”

Jennifer Cox

Only these prompts were not coming from the teacher. These were student-to-student conversations and they were powerful.

What possibilities open up in the classroom if we create the environment where many of the prompts, questions and connections made by teachers as they deliver instruction are generated by the students themselves? This was the question Richardson and I used to guide our thinking as we planned this lesson one Thursday afternoon.

Teachers across the Commonwealth are realizing the power of classroom conversations to deepen learning and create equal access to lessons for every student. According to nationally known teacher and writer Cris Tovani, carefully planned student discussion benefits include:

- stimulating higher-order thinking

- developing social and listening skills

- holding students accountable

- helping students retain and comprehend

- fostering respect for differing perspectives

- allowing opportunities for timely, meaningful, formative assessment and feedback, which helps students assess where they are in their own learning

Meyzeek’s Richardson adds there are benefits to developing positive classroom community.

“Students are more engaged and less likely to refuse to work when they are allowed to have academic conversations. Even students who struggle to persevere when they get ‘stuck’ are eager to work through a math problem and move to the next step if they have a partner with whom to talk it out.”

But that’s not all. There are clear connections to social-emotional growth when teachers plan for, model and hold high expectations for discussions as part of the student learning process.

“I love seeing caring behavior that develops when students practice coaching each other,” Richardson said. “Students crave positive feedback and when they become skilled at talking with one another, I don’t have to be the only teacher in the room. The kids learn from each other.”

Richardson’s observations in her classroom are echoed in research. In his book “Choice Words: How Language Affects Children’s Learning,” Peter H. Johnston explains that, through the use of language, teachers can “build emotionally and relationally healthy learning communities – intellectual environments that produce not mere technical competence, but caring, secure, actively literate human beings.”

This is exactly what 6th-grade Jefferson County Public Schools Assistant Principal Cassandra Woods hopes to see at Meyzeek as administrators, teachers, instructional coach and students embark on a learning journey together next spring about the power of words.

Teachers will plan for regular opportunities for academic discussion, modeling for students what it means and looks like to have professional conversations with one another. Students will practice and receive feedback on how to use academic vocabulary, appropriate tone, questioning techniques, critical thinking strategies and respectful language. All of these skills are what higher education and the workplace look for in graduating seniors.

“Students think more deeply and process more effectively through rich academic conversations. They are more engaged in the learning and the topic, all of the sudden, becomes connected and relevant to the student if he/she is able to talk and make meaning out of it,” Woods said.

I remember well the first student from my own classroom who showed me the power, access, and equity that student driven conversations can provide. “Andres” was a struggling learner from a single-parent household bustling with four brothers. English was his second language, he lived in poverty and his older brothers were said to have connections to gang activity. For the most part, Andres was a disengaged learner, concerned with things outside of school, angry and distrusting of the teachers trying to help him read and write.

Andres’ class and I were studying the theme of “A Poison Tree,” a poem by William Blake. I had practiced discourse structures with the students and they were ready to drive the conversation. My instructional coach and I listened intently as Andres’ questioned his classmates about whether or not they had ever been as angry as the speaker in the poem. What had happened? What had they done about it? Was the outcome fair and just? Why or why not?

My coach turned to me and asked if Andres was aware that he spoke about the poem like a scholar. A scholar. I kept him after class and shared the reason he earned the scholar label. He muttered a soft, blushing “thanks” and went to class. This was it! Talk was the key to unlock his learning.

Andres never again put pencil to paper without talking an idea through first. His scores improved, but more importantly, his learning confidence improved.

I saw Andres during a recent visit to his high school. When he noticed me, he straightened up, gave me a head nod and called, “Hey Ms. Cox, I’m still talking like a scholar!” There’s no doubt in my mind, Andres.

Jennifer Cox is the goal clarity coach at Meyzeek Middle School (Jefferson County). This is her 19th year in education and her first year in the Jefferson County public school system.

Leave A Comment