Willie Edward Taylor Carver Jr., an English and French teacher at Montgomery High School, was named the 2022 Kentucky Teacher of the Year on Sept. 9. As a child growing up in Floyd County, he recalls having limited access to the supplies he needed for school. The kindness he learned from the teachers who helped him as a child has led him to instill that same level of humanity in his classroom.

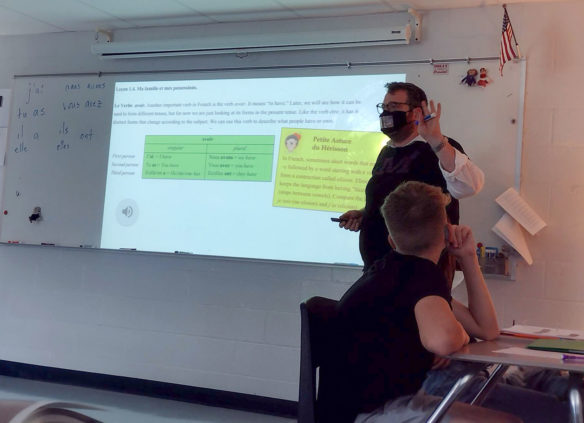

Submitted photo

As a child growing up in Floyd County, Willie Edward Taylor Carver Jr. recalls having limited access to the supplies he needed for school. Whether it was paper, pencils or even a pair of shoes, he knew he could rely on his teachers to help him get by.

“I remember teachers doing little things like offering me a pair of shoes and telling me little stories like, ‘Oh, my son couldn’t wear these and I thought maybe you would like them,’” Carver said. He now realizes the teacher had purposefully scuffed the shoes as to not make it obvious he was being gifted with a new pair.

“I had wonderful teachers who understood just how little resources most of the students in the school had,” he said. “I know there were Christmases where the toys in my house were purchased by my teachers.”

Teachers like Tammy Farmer, who Carver had in 4th and 5th grade, routinely went above and beyond to help equalize and level the playing field for their students.

“She had a way of finding the good in me when I didn’t see it, and making me see it,” he said. “Just that humanity is something to this day I think about.”

Now, as the 2022 Kentucky Teacher of the Year, Carver says instilling that same level of humanity in his classroom is pivotal to ensure learning is happening every day.

His passion for teaching comes from a single place, the belief in the dignity of his students and the desire to show them what they are capable of so that they, too, can understand their own worth, he said.

Before Carver ever stepped foot in a classroom, he already was an educator. As he tells it, there was never a moment when he didn’t know what he wanted to do with his life. Even back in his childhood, he said his teddy bears were the first ones to experience him as a teacher. Education has long been stamped in his soul, he said.

“My friends were always jealous because they said I was a teacher before I stopped having teachers,” he said. “Any moment we had, we would play school, and I was the teacher.”

After high school, Carver enrolled at Morehead State University (MSU), where he earned a bachelor’s degree in English in 2006 and completed the Master of Arts in Teaching program in English and French in 2009. Carver earned a Rank 1 in French linguistics from the University of Georgia in 2008 and completed post-graduate work in English at MSU in 2010.

His first official teaching job came when he traveled abroad to teach English at Lycée Cassini, a high school in Clermont, France, about an hour north of Paris.

“I had no clue what I was doing,” he said with a laugh. “To this day, I don’t know how I was able to manage that.”

According to Carver, the move across the Atlantic Ocean was so far out of his parents’ comfort zone that his father looked at him before he left and said, “If you mess this up, we can’t help you. You’re on your own.”

“It wasn’t that they didn’t want to help, but it was a reality check that I was in this alone,” he said. “I knew going into this that I had to make it work and I had to do it on my own.”

Living in a small village in Northern France, Carver found connections to the life he remembered in the Appalachian region from which he came.

“I thought it being an hour from Paris would make it vaguely metropolitan, but I was completely wrong, and I loved every minute,” he said.

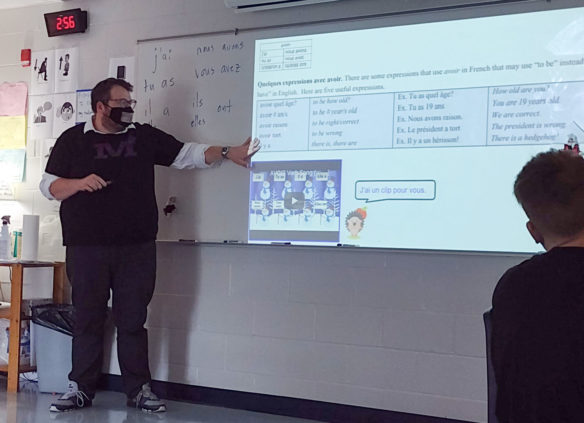

2022 Kentucky Teacher of the Year Willie Edward Taylor Carver Jr. says he often questions what is working to ensure the continuous growth of his students. Additionally, whether he’s teaching English or French, he always tries to connect his lessons to how students can apply them in the real world.

Submitted photo

Carver realized quickly that there is a “kinship in poverty.” His students lived in this small village and some of them had never been to Paris, though it was only a short train ride away.

“They had really strong regional accents that made them terrified to go places,” he said. “I thought, ‘I’m from Appalachia Kentucky, I get this. I understand you. You are my people.’”

During his time in France, he grew very protective of his students. On a trip to England, he recalled overhearing snide comments being made about them.

“I turned into a mother hen. I literally put my body in front of my students,” he said. “There are a lot of people on this planet who grow up not feeling like they belong or are capable, and that’s certainly not limited to Appalachia. That expanded my idea of what Appalachia is and what Kentucky is.”

Upon returning stateside, Carver found himself teaching French at the University of Georgia, before realizing his true calling was in the high school classroom.

“I really liked teaching college,” he said. “But I saw my students twice a week, and they were in their 20s. They needed me to learn French, but they didn’t really need much outside of that.”

Missing home, and knowing he had “a lot of heart to give,” Carver returned to the Commonwealth and began teaching English and reading at Raceland-Worthington High School (Raceland-Worthington Independent).

“Maybe there was even survivors’ guilt,” he said about his move back to Kentucky. “I sort of felt like I was in a beautiful place and thought about other people who could potentially go to beautiful places. Immediately my thought was, I really want to go back home.”

After spending a little over a year in Raceland, Carver became the French teacher at Montgomery County High School for one year before moving to teach English and French in Vermont.

Two years later, he would return to Montgomery County after a discussion with his husband at a Vermont café.

“We knew we weren’t going to live there forever,” Carver said. “He asked me if I could be a teacher anywhere on planet Earth right now, where would it be. I said Montgomery County.”

Now entering his ninth consecutive year as an English and French teacher with the district, Carver has no intentions of leaving.

As an educator, he often questions what is working to ensure the continuous growth of his students. Additionally, whether he’s teaching English or French, he always tries to connect his lessons to how students can apply them in the real world.

“I know sometimes the students feel a disconnect,” he said. “It’s really important that students have a voice. Even if it’s grammar exercises, I also make sure that students have a way to talk about what they think and how they see the world.”

A few years ago, Carver asked one of his classes on the first day of school, “What is English about and why are we even in this class?”

A student replied, “Knowing how to use a comma doesn’t take a needle out of my mother’s arm.”

“I think about that any time I’m trying to organize an assignment,” Carver said. “Before we even talk about commas, let’s imagine the cover letters they’re going to be writing. Let’s imagine the articles you might be writing. Let’s imagine what your future could look like and let’s prepare for that.”

Another way Carver has been able to connect with his students is through the formation of Happy Club, a student-led group that focuses on making the school a better place.

“Nothing excites me more than student initiative,” he said. “So I approached them, helping them develop ideas as we talked.”

Twenty-seven students showed up at Carver’s classroom in 2017 for the inaugural Happy Club meeting. The club outgrew his classroom, however, as membership quickly reached 40 students.

The club met weekly and had ambitious projects, Carver said.

Students distributed random messages at lunch, including recipes for biscuits, vocabulary words and facts about kangaroos. They gave out baskets for students to put extra breakfast food in for their hungry classmates and created a Post-It wall with affirmations. Students would sing songs and even send thank you notes to their teachers.

“The Happy Club had an impact,” Carver said. “The school literally became a lighter, less serious place.”

The most joyous aspect of the club for Carver has been witnessing a group of students, who otherwise would not have a club to go to, dance, sing and be silly and creative together. It was inspiration and fuel for him as a teacher, he said.

A year after its formation, Happy Club created a second club called Open Light, the county’s first inclusion club and outwardly LGBT-affirming club, Carver said.

“I can’t take credit for what my students themselves do,” he said. “But I can say that my goal is always to tell them that their dreams are never too big, and I remind them that the time to realize those dreams is now.”

Carver said the 2022 Kentucky Teacher of the Year award is his way of thanking all the teachers who supported him throughout his education journey.

“From the 5th-grade teachers who gave me food when I was hungry to the 4th-grade teachers who told me I could do anything to the kindergarten teachers who sat with me after school when I missed my bus,” he said. “All of these wonderful, hardworking people who are effectively the structural backbone of all of our communities who don’t get seen, it’s confirmation that everything they said was right. That where I come from, who I am, none of these things have any bearing on what I’m capable of.”

It now is Carver’s mission to take those lessons and pass them along to the students he has today as he works to shift their perceptions of themselves.

“Students see themselves as a kid from Floyd County or a kid from Montgomery County sitting in French class,” he said. “I want them to see themselves as someone who can do anything. That doesn’t mean they need to leave or go anyplace; it means that they need to experience life and believe that they are worthy of it.”

He is my amazing hard working fun loving caring giving Son and teacher I am so proud of him always have been this is just another accomplishment that makes him so special so proud of you Willie( SIE) carver so overwhelmed my cup runneth over love u with ever being of my heart

He is my brother in law and I am beyond proud of what he has done to achieve this award.