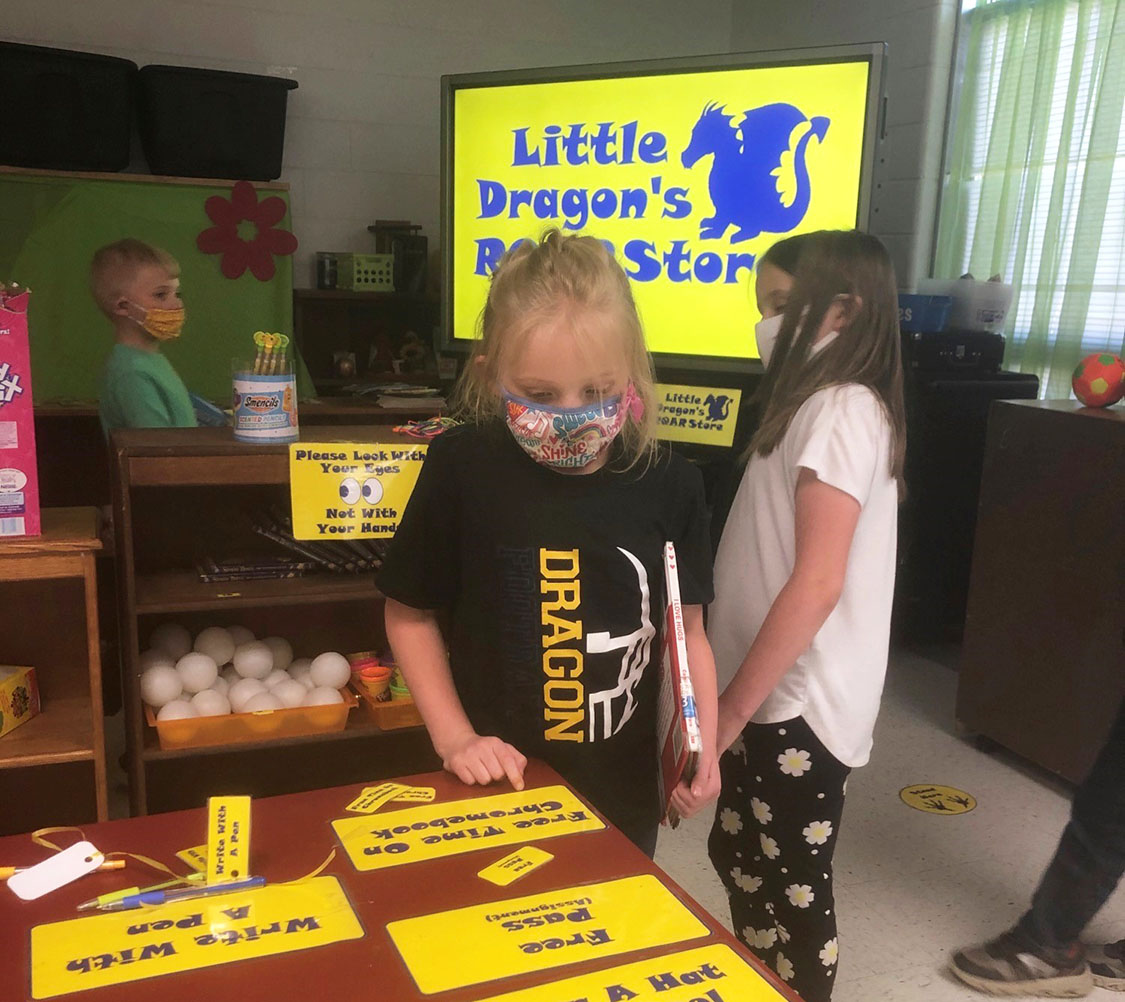

Pine Knot Elementary School students, from left, Brysen Sutton, Charley Kidd and Emory Estacio shop for rewards in the school’s “ROAR Store” with Dragon Dollars. Under the the school’s Positive Behavioral Intervention System (PBIS), students earn Dragon Dollars when they display appropriate school behavior.

(Photo submitted by the McCreary County school district)

The McCreary County School District wasn’t singled out for scrutiny in early 2020. The small district in southeastern Kentucky was just one of 10 randomly selected for state review each year.

In such reviews, multiple programs are examined, including those offered under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), generally known as special education, said Susan Burgan, parent involvement coordinator for the University of Kentucky’s Human Development Institute. Burgan is a member of the Kentucky Department of Education’s (KDE’s) consolidated monitoring team, but didn’t participate in reviewing McCreary County.

Monitoring teams conduct interviews and review records, she said. If any issues emerge, they are included in a report to the school district. The district then must write a corrective action plan (CAP) to address those issues, Burgan said.

McCreary County Superintendent Corey Keith said the outside monitoring team examined the district’s special education, alternative education and federal programs. As with any such comprehensive review, they found some items for improvement, he said.

Educators and administrators in McCreary County received the feedback and got to work immediately, Keith said.

“The bottom line is that they saw this as an opportunity to improve what we do for our children. That’s the bottom line for anything that we do,” he said.

The Report

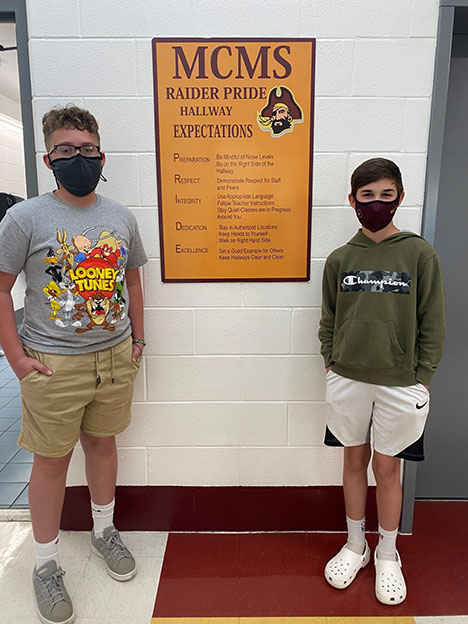

McCreary County Middle School students stand next to a hallway poster displaying the school’s Positive Behavior Intervention System (PBIS) expectations: Preparation, Respect, Integrity, Dedication and Excellence. The acronym is posted in many places and taught regularly to remind students of proper behavior, preventing disciplinary problems instead of reacting to them. (Photo submitted by the McCreary County school district)

Each year, KDE’s Office of Special Education and Early Learning (OSEEL) chooses one topic to focus on monitoring. The focus in 2020 was behavior and discipline. That includes handling student behavior and having a good system of Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) in place.

The McCreary County School District has about 3,000 total students in two elementary schools, one middle and one high school. About 520 students receive special education services, said Amelia Strunk, the district’s director of special education (DoSE). The relatively small size of the student population means the district may have been able to implement changes faster than larger school systems could, she said.

When the monitoring process starts, a “caravan” from various KDE offices and programs comes to the district, said Stephanie Ernst, preschool state transformation specialist in KDE’s Division of IDEA Implementation and Preschool (DIIP). The first meeting usually brings those KDE personnel and representatives of the school district together in a big room. KDE personnel come in with schedules to interview teachers and staff at all schools.

“It can be very, very overwhelming,” Ernst said.

McCreary County was the first district examined in 2020, Ernst said. From Jan. 14–16, a monitoring team from the OSEEL Division of IDEA Monitoring and Results (DIMR) and another from the DIIP examined policies and procedures district-wide.

The monitoring report arrived on Valentine’s Day, Feb. 14, shortly before COVID-19 shutdowns began, Strunk said. That timing benefitted McCreary County, allowing the district to pull together at once resources from multiple agencies that previously dealt individually with school districts, while the physical absence of students let work within buildings proceed unhindered, she said.

“It was a priceless opportunity,” Strunk said.

The Response

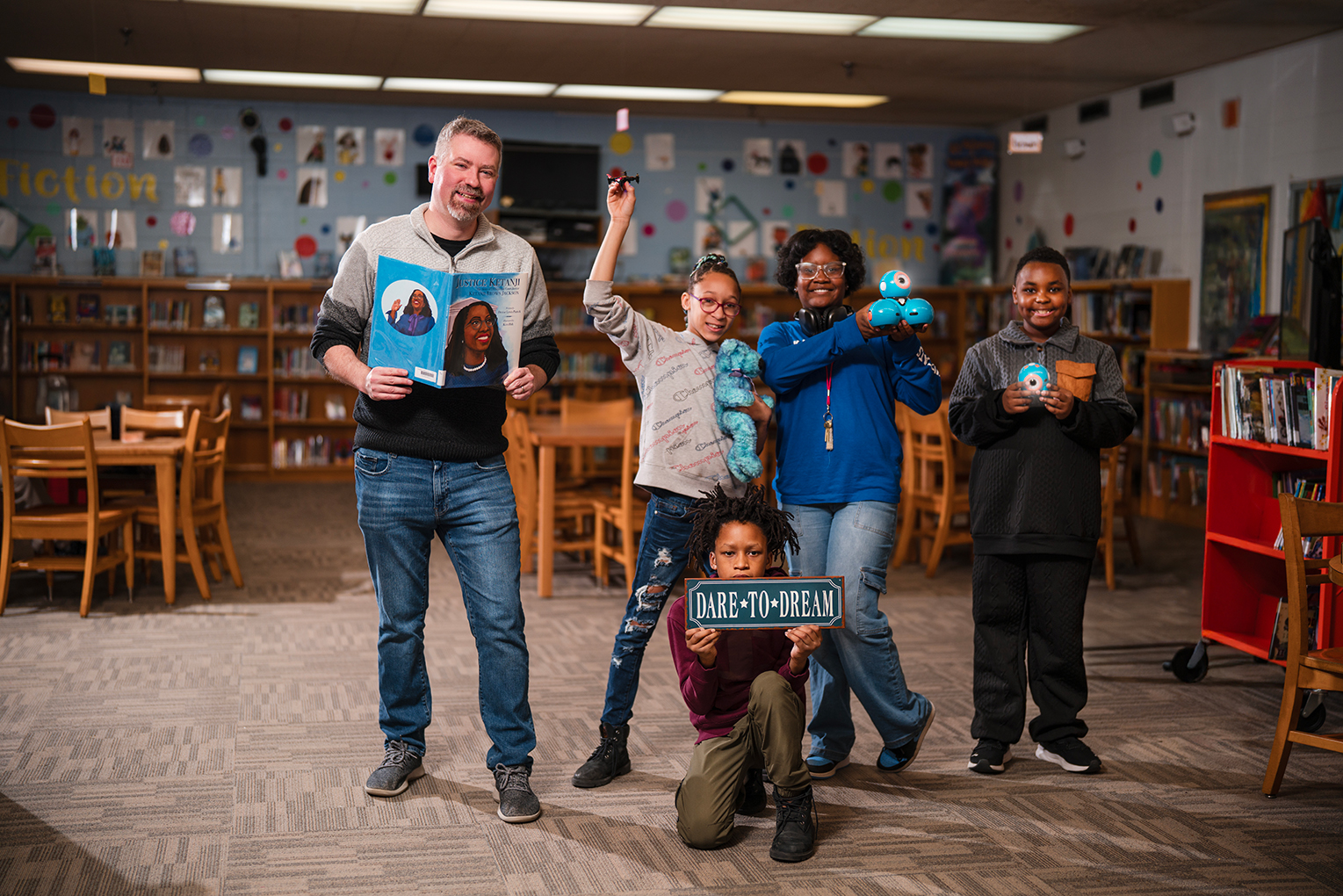

McCreary County Middle School students show off a banner displaying the school’s acronym for Positive Behavior Intervention System (PBIS) expectations: Preparation, Respect, Integrity, Dedication and Excellence. Such reminders are posted throughout the school, on the playground and on buses. (Photo submitted by the McCreary County school district)

Despite having to work during COVID-19 restrictions, McCreary County completed the steps in its preschool and IDEA CAP before the one-year deadline, Ernst said.

Items related to physical facilities were finished within three or four months, and were well documented, Ernst said. Preschool facilities had a year to come into compliance, and that deadline was met, too, she said.

The district took the review as an opportunity to change and prepare for the future, making sure it had appropriate policies and communication plans, and people in the right positions to implement them, Ernst said.

In April 2020, KDE reached out to McCreary County with the opportunity to partner with other educational entities through a State Personnel Development Grant, funded through the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Special Education Programs.

Participation was optional, but McCreary County agreed and formed a partnership with the DIIP, the Southeast/South Central Educational Cooperative (SESC), Berea Regional Training Center and the University of Louisville’s Kentucky Academic and Behavioral Response to Intervention (KY-ABRI). More assistance came through KDE’s P-12 linked teaming: general and special education teachers who provide training and coaching to implementation teams.

Together, they developed a district and school teaming process, collecting data to see what was needed to refine the district’s PBIS practices. Those agencies regularly collaborate with McCreary County schools, setting up a cohesive system to work in concert on the same initiatives.

“That, I think, is amazing,” Burgan said.

Patricia Joan Whitney, a Multi-Tiered System of Supports consultant at KY-ABRI, said Strunk reached out to her, Dusty Phelps at SESC, and the other partner agencies as soon as McCreary County received its report and asked for help.

“She created a phenomenal team of support where we all rallied for one purpose,” Whitney said.

Whitney said she and Strunk met every other week and consulted with the District Implementation Team (DIT) every month, which in turn met with Building Implementation Teams at every school.

To improve behavioral interventions, the DIT met monthly with its agency partners to analyze data and refine practices. The district also worked with its partners to provide professional development for teachers and school PBIS teams.

“They’re just really, really developing their staff to be able to maintain this system,” Burgan said.

The DIT members always leave meetings with an action plan, specifying who’s responsible for each task and how to measure progress, Whitney said. Action items are reviewed at the next meeting.

Actions Taken

Some districts, when told they have areas that need addressing, try to fix things without any help from outside, Burgan said. That’s not what McCreary County did.

“McCreary opened arms to people coming in to provide them with support,” Burgan said.

Many items in the report didn’t directly involve special education, though they did apply to it, Strunk said. They covered general changes to discipline and communication.

Many of those seemed like minor alterations but garnered major results, she said. Ultimately, the disciplinary changes supported students through intervention, managing actions at the classroom level instead of at main office level, Strunk said.

“We really drilled all the way down, to build the foundation from the bottom up,” Strunk said. One effort was to make sure data entered in Infinite Campus was accurate so educators could make better data-driven decisions, she said.

“That way, our approach now is proactive rather than reactive,” Strunk said.

Then McCreary County created teaming structures at the district and school levels to analyze that data and refine practices accordingly, Burgan said.

The revamp covered preschool through 12th grade, with staff from all levels involved, Strunk said. The district made an effort to include everyone from custodians to teachers to parents, she said.

“All of the training in the world is not going to be effective unless you have buy-in from all of your stakeholders,” Strunk said.

Everyone’s participation was positive, and some brought multiple ideas, she said.

McCreary County’s preschool needed work on its support and credentials, Ernst said.

The district was offered a PBIS coach from the Berea RTC, becoming the first district to use this. McCreary County has been very willing to let outside observers watch the training, becoming a model for continuing such work in other districts, Ernst said.

Positive Behavior Intervention and Supports are preventive interventions rather than reactive actions, Whitney said. All staff and students, including students with disabilities, benefit from knowing their schoolwide PBIS expectations, she said.

The county offered some PBIS prior to 2020, but the program has now expanded district-wide, Burgan said.

Methods are slightly different at each school, but they all promote positive expectations for students, Strunk said. Each school developed its own acronym for PBIS expectations, which are used in daily announcements and other promotions.

“You’re seeing a whole lot of energy invested in ‘How can I reward positive behaviors instead of focusing on negative behaviors and the consequences?’” Strunk said.

All the district’s schools have implemented the same PBIS language, Strunk said. A foundation has been built, but it will probably be several years before PBIS is fully integrated at all levels, she said.

In Retrospect

Andrea Craig, state transformation specialist in the DIIP, said she believes McCreary school officials now feel they’ve got support and can reach out to their partner agencies and KDE if they uncover barriers to learning in the future.

Craig said KDE will remain involved and offer support as long as McCreary County wants.

Without the commitment of Corey Keith, Amelia Strunk and other McCreary educators, Craig said she doesn’t know if this type of systemic change would have been possible.

Keith had particular praise for Strunk, whom he credited for work on PBIS and building partnerships.

“I’m blessed with a great one there,” Keith said – adding that Strunk always defers praise to her colleagues.

Superintendents, like other leaders, always hope that structures built under their watch will endure after they’re gone, he said. Strunk, Whitney and their collaborators have laid a foundation for success that will continue even when all district personnel have changed, Keith said.

Strunk, in turn, lauded CAP lead Jessica Jones from DIMR. Behind the scenes, Jones made sure momentum kept building and ensured documentation requirements were fulfilled for each item, Strunk said. Jones also offered Strunk constant encouragement and assistance.

Shirley Surface from SESC, who mentored Strunk from the start of her DoSE career, worked seamlessly with Strunk as well. The cooperative has always provided resources for McCreary County’s special education teachers and administrators, and quickly provided necessary information despite the COVID-19 disruption, Strunk said.

Misty Head, behavior coach from Berea RTC, focused on bridging the gap between PBIS in preschool and kindergarten, working to create a system to prevent problematic behavior from the beginning, Strunk said.

The district’s school psychologists, Missy Black and Kevin Morris, also were leaders in the District Implementation Team (DIT) meetings, Whitney said. Keith encouraged the district’s central office staff to work side-by-side with building administrators in reviewing data and implementing a multi-tiered system of support, she said.

The collaborative services provided to McCreary County are available to others, Burgan said.

“I’m hopeful that other districts will agree to take this kind of an opportunity to move forward,” Burgan said.

Very pleasing to see these improvements being made with attention to building a system that will endure over time and changing personnel. Having taught both Corey and Amelia in middle school years, its a delight to see the promising performance and character and personality traits they both showed then are resulting in positive effects for students now and in the future. Always, Best Wishes for and to McCreary County Schools: a place of good and great memories to Christine and me both, of our many years there.