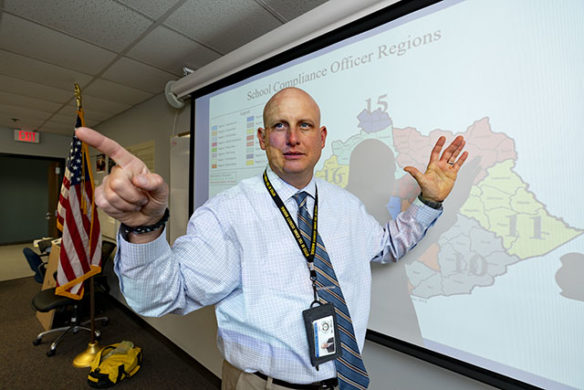

Ben Wilcox, Kentucky’s first state school security marshal, stands in Farristown Middle School in Madison County in August. 2019. Wilcox’s position was created in early 2019, when the Kentucky General Assembly passed the School Safety and Resiliency Act, known as Senate Bill 1 for that year.

Photo submitted

- Ben Wilcox is Kentucky’s first state school security marshal, appointed soon after the job’s creation in 2019.

- Wilcox and 16 school security compliance investigators conduct risk assessments of Kentucky schools and work with school administrators to comply with safety standards.

By Jim Gaines

jim.gaines@education.ky.gov

Ben Wilcox laughs a little when asked how COVID-19 has changed his job as Kentucky’s state school security marshal.

He hadn’t been on the job long when the pandemic hit. The position of state school security marshal had only been created in March 2019. Wilcox formally started work July 1 of that year, but a month earlier he began traveling the state to share information on Kentucky’s newly enacted school safety standards.

The same law that created Wilcox’s job mandates that all Kentucky schools must meet certain safety standards, as outlined in a 66-point risk assessment tool. He didn’t think it was fair to carry out full assessments while everyone was still figuring out how the new law worked, but he did want school officials to become familiar with the process. Wilcox and his 16 compliance officers fanned out across the state on Jan. 13, aiming to do an informal initial assessment in every Kentucky school by the end of the spring semester.

That ambitious schedule was derailed when schools shut down for in-person classes in March due to COVID-19. In the interim, Wilcox and his staff carried out plenty of training, but they couldn’t re-enter schools until May, he said. It took until mid-September for them to finish assessments at all of Kentucky’s 1,289 schools.

School staff generally are glad to hear from Wilcox and the compliance officers. That speaks volumes about Kentucky’s dedication to the safety of children, he said.

“I hear a lot more positives about our organization than I do negatives,” Wilcox said. “We’ve had an overwhelming positive response from the school community on what our office does.”

Wilcox said he sees his compliance officers not just as rule enforcers but also as coaches, preferring to help schools reach safety benchmarks rather than citing them for lapses.

“If we find an issue with your school, we’re going to work on getting that issue fixed,” he said.

New Standards and New Responsibilities

In early 2019, the Kentucky General Assembly passed the School Safety and Resiliency Act, known as Senate Bill 1 for that year.

It created the positions of state school security marshal and district school safety coordinator. The act also required assigning school resource officers (SROs) to each school, funding permitting, and established requirements on school building access, suicide prevention training, active shooter training, trauma-informed approaches to education, school counselors, student-involved trauma, terroristic threatening and creation of an anonymous threat reporting tool.

The law also mandated creation of a 66-point risk assessment tool. Districts aren’t legally required to report their assessment results until 2021, but Wilcox wanted to do an early practice run to introduce schools to the process and the people involved. The Kentucky Center for School Safety (KCSS) approved the final version after a draft was circulated among schools in late 2019.

“I will tell you this, I am so glad we started this run in 2019 and not 2020,” Wilcox said.

Wilcox pushed out the draft risk assessment months ahead of schedule so school officials could familiarize themselves with it, said Jon Akers, KCSS executive director.

The Kentucky Department of Education’s Superintendents Advisory Council was given a chance to review the Safe School Assessment document and asked for some revisions, which Wilcox heard and relayed to KCSS.

Lyon County Schools Superintendent Russ Tilford, a member, of the council, said that resulted in a better working document.

The risk assessment has three parts, Wilcox said.

The first covers compliance with safety features and policies that are directly related to funding approval for new construction. If schools aren’t compliant in those areas by 2022, that funding may be affected, he said.

The second deals with mandatory safety requirements which aren’t directly related to funding.

And the third is an opportunity for schools to share how they are implementing current trends in school safety. When one school implements new safety features or policies that work well, Wilcox’s office shares those with other schools around the state.

“We’d like to use that as a conduit for communication between school districts for what’s working for them on safety and security,” he said.

Compliance officers first do a scheduled on-site review of each school to establish a baseline. The second assessment will be unannounced. After about 18 months, final assessments will be combined into a state report and circulated statewide to share best practices.

This year, Wilcox doesn’t plan on starting safety assessments until mid-October. Most schools resumed in-person classes Sept. 28, and he doesn’t think it’s fair to carry out full risk assessments while educators are still figuring out how to work through COVID-19 safety precautions, he said.

Ben Wilcox, Kentucky’s first state school security marshal, speaks at the Kentucky Department of Criminal Justice Training during September in front of a map showing the districts his 16 compliance officers cover. All Kentucky schools must meet certain safety standards, as outlined in a 66-point risk assessment tool. Wilcox and his 16 compliance officers fanned out across the state on Jan. 13, aiming to do an informal initial assessment in every Kentucky school by the end of the spring semester.

Submitted photo by Jim Robertson

Choosing the Right Person

Wilcox has a bachelor’s degree in police administration and a master’s in career and technical education with a concentration in occupational training and development from Eastern Kentucky University (EKU).

He became a school resource officer in 1999 as a Montgomery County Sheriff’s deputy in the wake of the mass school shooting at Columbine High School in Colorado.

Wilcox joined the Kentucky Department of Criminal Justice Training (DOCJT) in 2004. In 2019, he was supervisor of DOCJT’s Instructional Design section, responsible for the agency’s testing, curriculum, lesson plans and instructional material.

But he had told his boss, then-DOCJT Commissioner Alex Payne, that he was interested in working on school safety. So after the state School Safety and Resiliency Act created the job of state school security marshal, Payne appointed Wilcox to the job with approval from the Justice and Public Safety Cabinet and the governor’s office. Current DOCJT Commissioner Nicolai Jilek maintained Wilcox’s appointment.

The job of ensuring compliance with the School Safety and Resiliency Act might have fallen to KCSS, but Akers opposed that as the bill was being written. He said that’s because it has taken him nearly two decades to get superintendents comfortable with the idea that KCSS is there to advise them, not judge them. Putting the center in an enforcement role could have damaged that carefully built rapport.

The next-best fit for the job was the DOCJT, Akers said. He told then-Commissioner Payne that whoever was selected as state school security marshal had to be sensitive enough to educators’ concerns to work with them, rather than “hammer” them into compliance.

“Ben has been masterfully cultivating relationships around the state with superintendents and principals,” Akers said. “And he’s done a really good job of training up his compliance officers on the same philosophy.”

If risk assessment turns up problems at a school, compliance officers will coach the local leaders on ways to fix things.

More than a year later, Akers is confident Wilcox and his compliance officers have succeeded in showing schools that they’re all on the same side.

“Commissioner Payne couldn’t have picked a better guy,” Akers said.

Organization and Action

Wilcox oversees 16 school security compliance investigators, each assigned to a geographic district. His office also includes three investigator managers, first-line supervisors who each have four or five of the compliance officers assigned to them. The investigator managers do school assessments themselves, but also check paperwork, approve work time and provide general support to their compliance officers.

Compliance officers must be former law enforcement officers with investigative experience. Each compliance officer works from home but must live within or near the region for which they are responsible.

Wilcox began interviewing 300 applicants in August 2019 and had filled the 16 compliance officer jobs by that November.

“We were blessed to have a lot of very qualified applicants spread out all over the Commonwealth who were interested in these positions,” Wilcox said.

Tilford said Wilcox and his compliance officers very approachable and he and Wilcox talk five or six times a year.

“Ben and I will sometimes just bounce things off each other informally,” he said.

On a day-to-day basis, Wilcox stays in touch with his compliance officers and fields questions from schools.

“And that keeps me extremely busy,” he said.

Consistency is a point of pride for Wilcox: If schools at opposite ends of the state ask their assigned compliance officers the same question, they will get the same answer. He meets with officers every Friday to discuss what issues are regularly coming up.

Wilcox said he wants his staff to build relationships with the schools to which they’re assigned so that schools feel free to call them at any time with questions, knowing that officer will be on the scene the next day.

“We are here to serve, even though we are also here as compliance officers,” he said.

Changes and Questions

Wilcox’s work already is producing results. Based on the initial informal assessment, Lyon County plans to replace the doors on a gym that also serves as a physical education classroom and make some procedural changes, Tilford said.

One thing school officials statewide have asked is whether they can open classroom doors and windows during class for better ventilation to help prevent the spread of COVID-19. In June and July, Wilcox met with the Kentucky Department for Public Health (DPH), the Kentucky Department of Education and EKU on the subject. EKU has been conducting training for educators on HVAC.

Wilcox’s office now has authority to grant exemptions to security guidelines as a public health measure, under certain criteria. But after consultation with DPH, it was decided that the possible benefits of ventilation from having interior doors open do not outweigh safety concerns, Wilcox said.

Accordingly, his office has not issued any exemptions allowing those doors to be open during instructional time.

Outside windows can be opened to improve airflow, and classroom doors can be opened before and after school and between classes, Wilcox said.

Akers said he and Wilcox consult regularly on issues, making sure their messages to schools are consistent.

“Ben and I talk on average probably three times a day,” Akers said. “My office and his office work hand in glove.”

If a school needs help complying with security standards, KCSS will provide consultants.

For Wilcox, working through issues as they arise brings a deep satisfaction, especially in times made tougher by COVID-19.

“That’s the biggest thing about this job, that I’m excited about it every day. There’s something new every day,” he said.

Leave A Comment