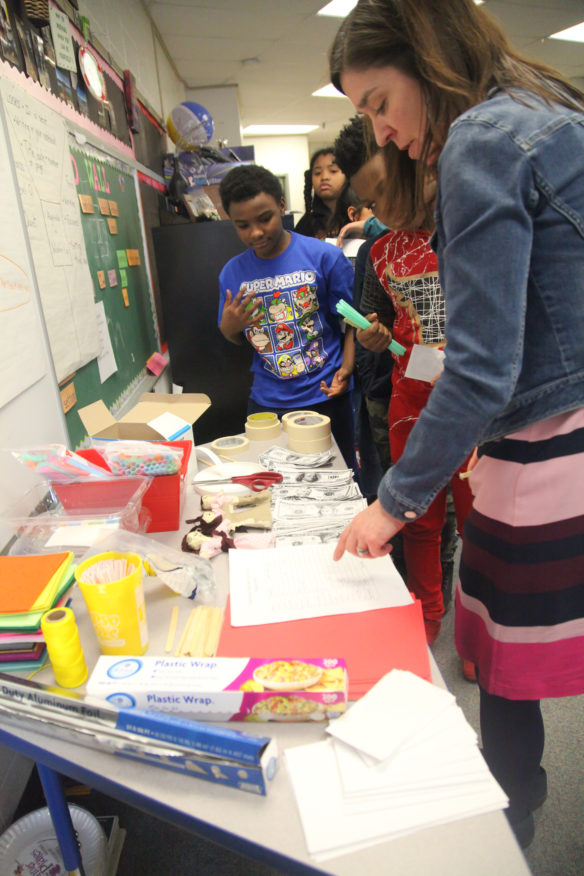

Jennifer Stith, the gifted and talented magnet coordinator at King Elementary School (Jefferson County), helps 3rd- and 4th-grade students obtain the materials they need to build beds for a doll as part of a project for gifted and talented learners. A grant from the U.S. Department of Education helped King Elementary and four other schools in the district identify and serve more gifted students from underserved populations.

Photo by Megan Gross, March 11, 2019

- The federally funded project provided for professional development for primary teachers at five schools, and it could have an impact well beyond Jefferson County.

- The project has ended, but some of the participating schools are continuing the work and it may be expanded within the district.

By Mike Marsee

mike.marsee@education.ky.gov

It was extremely noisy in Jennifer Stith’s classroom, and it was music to her ears.

Students were talking in groups of two or three and moving freely around the room as they worked on the project Stith had given them. It would have been a much quieter space not so long ago, however, because most of the gifted and talented students Stith was working with wouldn’t have been there.

In five Jefferson County elementary schools, the number of students who have been identified as gifted has risen significantly thanks to the Reaching Academic Potential (RAP) Project. The four-year project was funded by a federal grant that helped to identify and serve students in underserved populations.

“When the program started here, we had three advance program students by district standards, and we’ll have 27 in our building by the start of next year. That’s how rapidly in three years our identification process has worked,” said Stith, the gifted and talented magnet coordinator at King Elementary School (Jefferson County).

“I think one of the biggest things is that it opens doors, it gets people to look at things a little bit differently,” said Stephanie White, the principal at King Elementary School. “If there are teachers or other individuals who felt like only one particular type of child could qualify for gifted education, I think this really helped to break that stereotype. We helped break the mold and find different ways to identify those students.”

KDE partnered with the University of Louisville, Western Kentucky University and Jefferson County schools in the project, which utilized the Young Scholars Model developed by the Fairfax County, Va., schools at five elementary schools.

In those schools, all teachers in grades K-3 received professional development in gifted education, and one teacher from each school was supported through the grant to earn a gifted and talented endorsement so they could serve gifted instructional leaders at their schools. The schools were measured against five other schools in the district that did not receive those supports.

Kathie Anderson, KDE’s gifted and talented consultant and the project director for the grant, said the project has had a tremendous impact on both staff members and students.

One of the primary goals of the RAP Project was to help reduce Kentucky’s growing excellence gaps, which are differences in scores at the advanced level among groups of students that are typically underrepresented in gifted classes. That could be due in part to factors such as poverty, negative peer pressure, bias and discrimination.

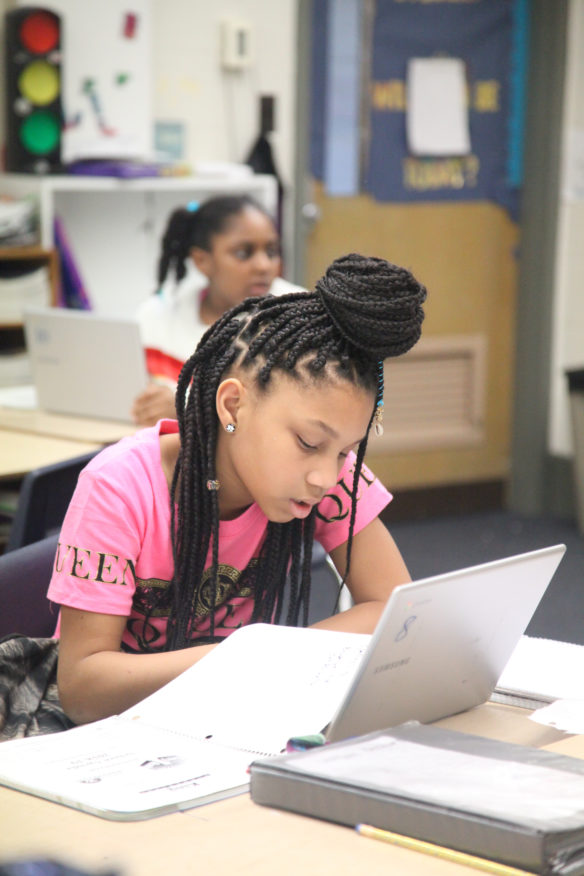

Two students at King Elementary School (Jefferson County), part of a group of gifted and talented students who are brought together for instruction, collaborate on a project in which they will build a bed for a doll. The school had three students in an advanced program for gifted students in 2015, which was the start of a four-year project that has helped the school identify and serve more gifted students from underserved populations. There will be 27 students in the program when the 2019-2020 school year begins.

Photo by Megan Gross, March 11, 2019

In the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) given to Kentucky students in 2017, 11 percent of 4th-grade students who did not qualify for free or reduced-price meals scored at the advanced level in mathematics, compared to 4 percent who did qualify. Similar excellence gaps are found within all NAEP results in every content area and grade level tested.

“There’s been a huge misconception that gifted kids are just going to score Distinguished on their own or excel on their own, but without pushing them, they’re not,” said Lindsay Dotterweich, a 3rd-grade teacher and the gifted and talented lead at Gilmore Lane Elementary School. “We’re realizing we have a lot of gaps to close in gifted education as a whole, but also across socioeconomic backgrounds.”

“What we hope is that we are building the capacity of teachers – especially of the teachers we’ve worked directly with at our five project schools – to first have an understanding of what we call underrepresented students and to have an awareness that these students can also be gifted, but they may show their giftedness in ways that may be different from advantaged students,” said Mary Evans, the program director at WKU’s Center for Gifted Studies.

In the project schools, that started with professional development and a recognition that it’s important for school leaders to be knowledgeable about excellence gaps and what should be done to close them. Evans said professional development focused on what gifted students look like, characteristics of underrepresented students that might be different and classroom management techniques that support differentiation.

“It’s some of the best professional development I’ve ever received,” Stith said.

There also was an emphasis on new ways to look at giftedness and why it might not always be reflected in a test score.

“We saw early teachers saying, ‘We really want to do this, but our students are having difficulty managing their behavior at learning centers,’” Evans said. “We looked at different ways to assess students, and one of the things we’ve done is we’ve used response lessons rather than the traditional paper-and-pencil kind of test. The response lessons were developed to tap out more culturally responsive behaviors, such as sensitivity and creativity. Our PDs showed real samples of student responses and showed teachers how to recognize giftedness in those responses.”

The Cognitive Abilities Test (CogAT) is used throughout the Jefferson County schools to identify 3rd-grade students who will receive gifted education services, but Stith said students at King Elementary are now being identified much earlier through those response lessons.

“It’s just getting the kids to think outside the box,” she said. “One 1st-grade lesson uses dots. I give them dot stickers and they randomly put the dots on a piece of paper, and from there they have to create a picture from the dots. If they can take the dots and make an amazing picture, that’s an example of intelligence.

“By 3rd grade we still have to administer the CogAT, but I start working with kids in pull-out settings in 1st grade. I pull them into groups and do enrichment, things like writing haikus. It is amazing what they are really capable of when you give them a little belief.”

On one recent day, Stith’s students were building beds for a doll. The exercise started with one of Aesop’s fables, “The Fox and the Cat,” and students were tasked with building a bed that would support the homemade doll’s weight with materials made available for them to “purchase,” such as frozen pop sticks, straws and felt squares. They were given a fixed amount to spend and were left to design a bed and determine the materials they need before buying and building.

“I love the excitement in the room. Right now you can feel it,” Stith said. “They’re all focused. It’s noisy, but they’re thinking, they’re focused.

“It makes me want to continue to do this, as much as it’s stressing me and I’m being pulled in a million different directions. None of them are off task in a bad way. They’re all focusing and thinking and building, so to me that’s exciting.”

A student at King Elementary School (Jefferson County) works on a budget for building materials as part of a project for gifted and talented students in Jennifer Stith’s classroom. A primary goal of the project to identify new gifted students at King Elementary and four other schools in the district was to help reduce Kentucky’s growing excellence gaps.

Photo by Megan Gross, March 11, 2019

Students that are identified for the primary talent pool are clustered – not tracked, Stith stressed – into groups with like-minded peers to increase their differentiation and help them qualify for further opportunities down the road. A number of those students are English learners, who are being identified at a much higher rate than before. “A lot of them look like struggling students sometimes, so the project taught our teachers things to look for in different populations that could potentially show their giftedness,” Dotterweich added.

The work continues in Jefferson County. though funding covered the project for only three years.

“I definitely see this work continuing in the schools that have already vested in it, and we have taken it to the district level to expand it to more elementary schools. We even have a couple of middle schools interested,” said Labron Horton, the gifted and talented education coordinator for Jefferson County schools.

Dotterweich said there is interest in other parts of the state as well.

“There’s definitely a lot of people out there in rural districts that are looking for ways to improve their gifted education systems, and having a full-blown project makes it a little more replicable for other districts,” she said. “We’re definitely trying to promote this as an effective way to serve gifted kids when there aren’t a lot of resources available.

Dotterweich said the project’s greatest impact might be in increasing awareness of gifted students in underserved populations.

“The biggest impact of the project is just widening our definition of giftedness and how that looks in different populations of kids,” she said. “We always talk about our struggling learners, but every kid deserves to learn something new.”

MORE INFO …

Lindsay Dotterweich lindsay.dotterweich@jefferson.kyschools.us

Mary Evans maryameliaevans@gmail.com

Labron Horton labron.horton@jefferson.kyschools.us

Jennifer Stith jennifer.stith@jefferson.kyschools.us

Leave A Comment