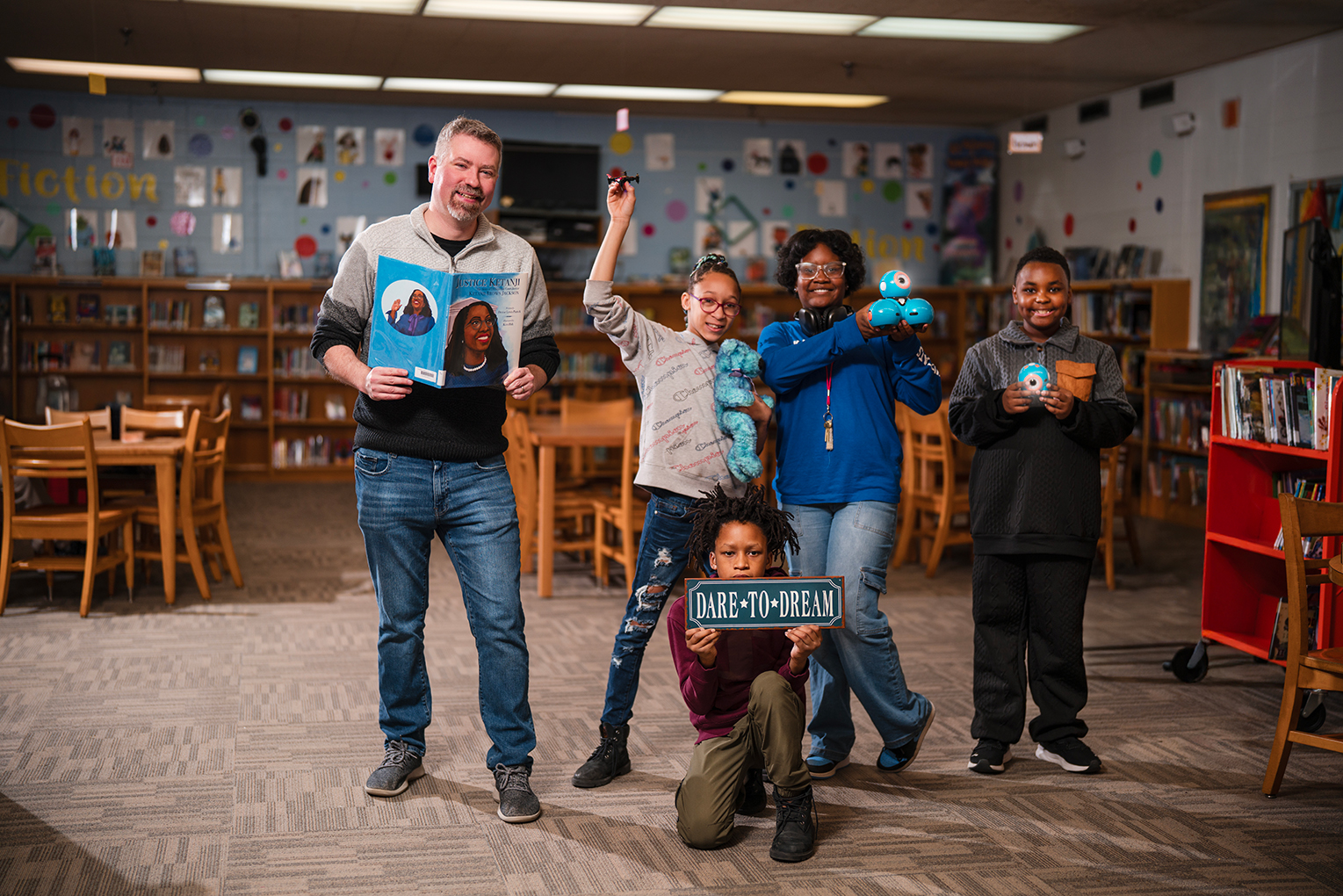

Montgomery County High School senior Nolan Walters, junior Shane Fauzey and senior George Hamilton stand back as cattle pass at the Chenault Agriculture Center.

Photo by Amy Wallot, April 11 , 2013

By Matthew Tungate

matthew.tungate@education.ky.gov

Montgomery County school district students have no beef with eating locally-produced meat. And agriculture students at Boyle County High School feel the same way when it comes to sharing the fruits of their labor with their school cafeteria.

All puns aside, students in both Montgomery and Boyle counties are enjoying being part of agriculture programs at both high schools.

Montgomery County High School’s agriculture program has delivered 6,000 pounds of locally-raised beef this year to the district’s cafeterias, according to agriculture teacher Jeff Arnett. The school has been growing lettuce for the district for several years, he said, and the district’s food services director wanted to expand into beef.

Fellow agriculture teacher Alton Stull said students who worked with the cattle were very proud when the school served locally-produced hamburgers for the first time in October.

“You could really see a sense of pride in our students who had been in those classes and had the opportunity to do hands-on work with those animals, and see how all that work came full circle. They got to see the finished product there in the cafeteria,” he said.

Arnett said the district has 90 female cows on its 293-acre farm. Before this year, the agriculture department sold cows to a stockyard for market price. Now, instead of selling the cows to the stockyard, the animals are slaughtered, processed and sold to the district. Everything except the steaks, Arnett said, which are sold separately by the agriculture department.

While the agriculture department is just one of the district’s suppliers, Arnett said the local beef is the best. That’s because most ground beef is made from 11- or 12-year-old cows getting too old to produce calves. But Montgomery County slaughters 18- to 20-month-old cows once they reach about 1,300 pounds, he said.

Students work with the cows and calves, vaccinating and halter-breaking them, he said.

“The students are out there quite often,” he said.

Students took a field trip to the packing plant so they would know how the animals are processed, Arnett said. Most students in the agriculture class do not live on a farm and don’t know where food comes from, he said.

Toni Myers, a National Board Certified agriculture teacher at Boyle County High, runs into the same issue. A lot of her students don’t garden, so she helps teach them to provide for their own families.

“We’ve kind of missed a generation or two of raising their own food,” she said.

For the last few years, Myers’ students have sold Bibb lettuce grown hydroponically, meaning without soil, in the school greenhouse. In March alone the school sold the district 200 heads, she said.

“Every head that we raise, they put into school lunches,” she said.

The program began in 2008 when the district’s food services director asked Myers if she could grow lettuce as well as what the district was buying from a Kentucky grower.

Myers said she and her students began trying to grow the lettuce in 2009 and weren’t having much luck. So she contacted the local agriculture extension agent and a horticulture agent from the University of Kentucky to help.

Myers said one or two FFA, formerly Future Farmers of America, members grow the lettuce, and her greenhouse class monitors it every day for pests and damage. It takes 55 days before the lettuce can be harvested, she said, and she has to work hard to not let it dominate her time. The district could buy five times as much lettuce as it currently does, Myers said.

Besides the lettuce, the school sells the district cherry tomatoes in the winter and is raising food this spring to donate to the local Family Resource and Youth Service Center’s weekend backpack program for 30 needy families.

But there is more to supplying fresh food to schools than just growing, Myers said. Here greenhouse club is certified to handle the lettuce which is Kentucky Proud certified.

Matt Chaliff, state FFA executive secretary and Kentucky Department of Education agriculture consultant, said food safety is an important issue not just for students growing food but school food services staff in handling and preparing it.

Cafeteria workers have to deal with raw produce that aren’t canned, pre-washed or pre-packaged, he said.

But the results of using fresh foods are worth it, Chaliff said.

First, students are learning to grow their own food. Hopefully, five to 10 years down the road those students will produce their own gardens and provide healthier foods for their families, he said.

“They’re getting the science that goes with that and, in a lot of cases, they’re getting business skills related to the input costs and what they’re selling the vegetables for,” Chaliff said. “So they’re getting a lot of skills beyond just how to grow a head of lettuce.”

Student health also is improving because they are eating more fruits and vegetables, he said. And healthier students miss fewer school days and get more out of school.

“Our students are so into convenience foods and eat so much food that’s prepackaged and premade. All the research shows that the more processed food is, the less healthy it is. So the more we can get students to eat food that is fresh out of a greenhouse or fresh out of a garden or fresh off the farm, the healthier they’re going to be,” Chaliff said.

Fresh food tastes better and has more nutrients, he said. So students may be more likely to eat the healthier food and develop lifelong good eating habits, Chaliff said.

Many districts could produce their own food, he said. But food service directors have to be on board. They have to be willing to make it financially viable for the agriculture department but competitive for the food service budget, he said.

Myers agreed, saying interested agriculture teachers should approach their local food service director and ask what would work for them.

“Find the need in your school, and then try to meet it in your greenhouse,” she said.

MORE INFO…

Kentucky Department of Agriculture Farm to School

Matt Chaliff, matt.chaliff@educat

Leave A Comment