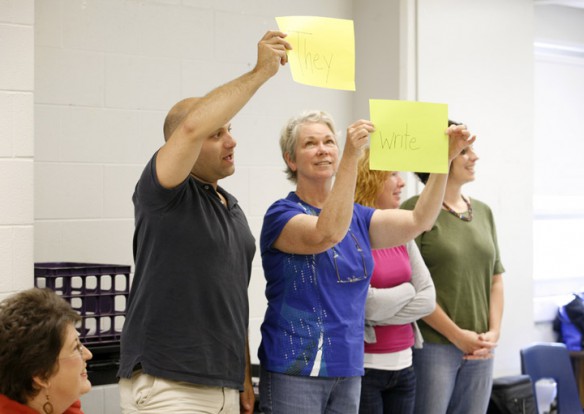

University of Louisville MAT student Jason Cooper and Jeffersontown Elementary School (Jefferson County) teacher Fife Wicks participate in an activity about subject-verb agreement during the Grammar for Teachers professional development at Westport Middle School (Jefferson County).

By Matthew Tungate

matthew.tungate@education.ky.gov

When Lynette Ward was in high school, one of her teachers asked the class if it wanted to do a second unit on debate or one on grammar. The class picked debate, of course, said Ward, now a 6th-grade language arts teacher at Bullitt Lick Middle School (Bullitt County).

Ward said she never received a good education in grammar, which presented a problem since it is littered throughout the Kentucky Core Academic Standards for English/Language Arts.

“I was nervous because I felt like I didn’t have the instruction,” she said. “So I’m going to be learning a lot with my students. But it’s important, because I want to sound intelligent and I want them to sound intelligent.”

Patti Slagle, a retired English teacher from Jefferson County, said Ward is not alone.

“A lot of teachers did not have direct instruction when they were students, and they certainly did not have direct instruction when they were in college,” she said. “So there are some teachers who are concerned about teaching this content because they don’t feel they have a strong command of grammar for instructional purposes.”

Slagle was doing her part last month to change how teachers felt about teaching grammar and their methods as part of a two-week workshop sponsored by the Louisville Writing Project. Slagle said 16 teachers from Jefferson, Oldham and Christian counties and Eminence Independent school districts and several students seeking their master’s degrees in teaching from the University of Louisville signed up for the workshop.

Slagle said teachers should not feel uncomfortable teaching grammar even if they don’t feel strong in its technicalities. That’s because grammar should be taught “in small bites,” she said.

“When you do that, even if you don’t have thorough command of the skill, when it’s broken down into small, scaffolded increments, you can learn along with your kids, which isn’t such a bad thing,” Slagle said.

Renewed interest because of new standards

Slagle said she recently conducted professional development workshops in Carroll, Kenton and Meade counties, and teachers agreed that scoring rubrics for the writing portfolios gave the impression to some teachers that grammar had decreased in importance. She said the scoring appeared to focus more on word choice, sentence variety and development of ideas because conventions, including grammar, appeared at the bottom of the rubric.

“There’s definitely a renewed interest in grammar because of the new standards,” she said.

Synthia Shelby, secondary literacy consultant at the Kentucky Department of Education, said Kentucky’s previous standards included grammar, but that the new standards help teachers be more intentional and specific when teaching grammar at various grade levels.

“Grammar has always been there,” she said. “We’ve always needed to teach it.”

The new English/language arts standards, used for the first time last year, are labeled “language” rather than “grammar,” but grammatical standards are included in every grade, Slagle said.

“When we look at the grammar standards for kindergarten, 1st grade and 2nd grade, there’s some really heavy-duty material there,” she said

For instance subordinate conjunctions are introduced in 3rd grade, Slagle said.

Annette Easton, an 8th-grade English and language arts teacher at North Drive Middle School (Christian County), said she was anxious after seeing the word “subjunctive” in the standards because she knew the focus had not been on grammar before and she was worried about covering the subject thoroughly and appropriately.

Easton said she wanted to attend Slagle’s workshop so she could learn to teach grammar in the context of reading and writing, just as the new standards expect.

“I’ve been trying to get there for a number of years,” she said.

From worksheets to writing

Slagle said about 100 years of research shows that teaching “traditional school grammar” – memorizing terms and rules, exercises and worksheets, and diagramming sentences – doesn’t transfer to students’ writing. She has taught students that way, she said, using the “drill and kill” method.

“There were a lot of kids in my class, for whom that just went right over their heads,” she said.

Unfortunately, this research was misinterpreted, Slagle said.

“I think what the research indicates is not that you don’t teach it, but how you teach it,” she said. “Kids don’t learn it if you teach it with memorization and out-of-context exercise worksheets.”

Now there is a model that is much more interesting. The new model treats grammar as a craft of writing, not as separate from it, she said.

Now, when teachers and students talk about word choice and sentence variety, they’re also talking about grammatical structures, and helping the students make intentional decisions, Slagle said.

“We’ve contextualized grammar study,” she said.

Shelby, who attended the Louisville Writing Workshop 10 years ago, agreed.

“Over the years we’ve taught grammar out of context,” she said. “But the use of these standards is reminding us that we have to use grammar as a tool to help with reading, writing, speaking, listening and beyond. So if it’s not used out of context, kids will have a better feel for why grammar is used in a book or why grammar is used in their writing.

“It should never be taught in isolation.”

Slagle remembers hearing the idea of teaching grammar in context as early as 1982, but she was not aware of a model for doing so. That is what she wanted to provide the teachers during her workshop.

One way is for teachers to use text students are familiar with and find a sentence or passage that emphasizes a grammar feature. The teachers and students focus on the sentence and see what the writer has done to make it effective. Slagle had the teachers in the workshop look at a passage in present tense, and then asked them to rewrite the passage in the past tense to see how it changed the meaning and tone.

“They were doing close analysis of the text, which really supports reading comprehension,” she said.

Slagle also encouraged teachers to find examples from books students are reading. Students groan when teachers say they are going to do a grammar lesson, she said. But if that lesson uses examples from The Hunger Games, for instance, “it really is a helpful motivational tool and can be very effective.”

Most importantly, Slagle said, is that teachers not separate grammar from reading and writing.

“You don’t try to carve out a piece of time to teach grammar,” she said. “But when you’re teaching reading and when you’re teaching writing, you do your grammar lessons with the reading that the kids are doing or with the writing that they’re doing. So you do it right alongside what you’re already teaching.

“We want to teach kids to read like writers and write like readers.”

Stacy Geyer, a 10th-grade English teacher at The Academy at Shawnee (Jefferson County), said she is going to be a lot more positive in her approach to teaching grammar. Rather than teaching a rule and then asking students to correct bad examples, she’s going to find good sentences and ask students to find what’s right in them.

“Hopefully they’ll find what’s right in their writing,” Geyer said.

Ward said she feels much better about teaching grammar after attending the workshop.

“Now what we’re going to do is pull out some awesome examples of great sentences, and we’re going to have them look at (them), and then we’re going to have them come up with their own rules and then take it back to their own writing in their own notebook and see if they’re using the rules, and if they’re not, they’re going to fix it,” she said.

Easton said used to tell her 8th graders that they could stop doing grammar worksheets when they could show in their writing that they had mastered the rules.

“But I didn’t know how to help make that connection for them,” she said. “So the one I should have been talking to was myself.”

MORE INFO …

Patti Slagle, slagerman@insightbb.com, (502) 893-2166

Synthia Shelby, synthia.shelby@education.ky.gov, (502) 564-2106

Leave A Comment