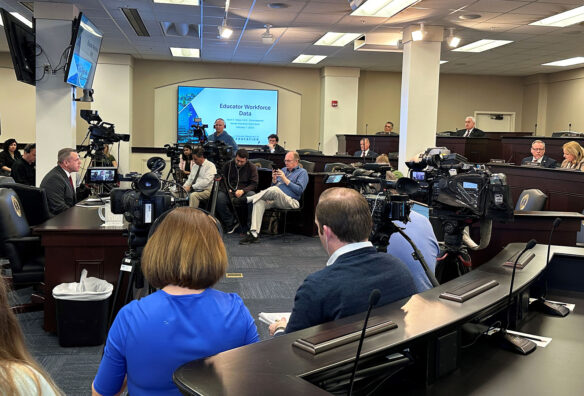

Kentucky Education Commissioner Jason E. Glass presents to the Kentucky House Education Committee about the education workforce on Feb 7.

Photo by Toni Konz Tatman, Feb. 7, 2023

The following is the testimony Kentucky Education Commissioner Jason E. Glass gave to the Kentucky House Education Committee on Feb. 7 about the educator workforce.

As some of you may know, I am a third-generation Kentucky educator. Both of my parents and my grandmother were Kentucky teachers. My sister is a teacher in Warren County, and my wife teaches in Fayette County. And when you are the commissioner of education and you are married to a teacher, you want to talk about accountability. I have accountability. So when it comes to teaching, this is our family business and something I care deeply about.

I know it is also something that you care deeply about – everyone has an interest in making sure that their community’s schools have an abundance of quality supported, professional educators.

There has been a lot said about the status of the teaching profession. With my time with you, I hope to present you with some data that we have on the current state of the teaching profession in Kentucky in hopes it will be informative to you as you deliberate further.

I know representatives of the Kentucky Association of School Administrators Task Force will bring recommendations and action steps, so I will avoid going into that area – rather, consider this a high-altitude look at the numbers relating to the educator workforce (or labor market) in Kentucky.

The pressures on the educator labor market is layered. However, one way to think about it is in terms of how many educators are coming in, how many are leaving and when, and what steps schools are taking to solve what is a growing shortfall between the two.

Over the past 10-15 years, we have seen a decline of about a third of teachers entering the profession, according to the American Association of Colleges of Teacher Education, which represent schools that prepare educators around the country. But we also know that the teacher workforce is highly state specific –meaning that most teachers in Kentucky come from Kentucky. While there are some state line crossers (both coming in and going out) that are part of the educator workforce, the vast majority of Kentucky’s pipeline for educators come from within the state.

In terms of teacher preparation numbers, we’ve seen some stability over the past five years. This is not to say that this stability has been uniform. The University of Kentucky (UK) and Western Kentucky University have increased their program numbers while other programs around the state have largely dropped enrollment. We also see a modest increase in the number of alternative pathway completers, the vast majority of which come through what is known as our “option 6 programs,” which are tied to universities.

Former UK Dean Julian Vasquez Heilig told me that while UK has been successful increasing the numbers in their program and in completers, he was having an increasingly difficult time getting those graduates to take teaching jobs in Kentucky, ostensibly due to other potentially better paying job opportunities available.

A bright spot in Kentucky and something contributing to the relative stability we see in our preparation programs is the increased enrollment in both the Teaching and Learning (T&L) career pathway and the Educator Rising career and technical student organizations at Kentucky’s high schools.

Current enrollment in the T&L Pathway has grown to more than 2,000 students and there are now 102 Educators Rising chapters across the Commonwealth. This year’s Educators Rising competition is expecting double the number of attendees and triple the number of competitors compared to last year! This effort is part of a larger statewide effort called GoTeachKY, which has been operating since Commissioner Wayne Lewis held my post, and something we can clearly see paying dividends now.

While we have been holding steady in terms of the candidates entering the profession, our challenge is in the increasing number of openings across the state and the inability to have strong choices at hiring time, or possibly positions going unfilled completely.

Kentucky’s teacher turnover rate – which is the percentage of teachers that do not return to teaching or new teachers that leave before the end of the school year – has been growing on an almost yearly basis. A good national benchmark for this number is around 15%-16%. Kentucky regularly hovers above this number and last year we saw a new high, passing 20% in teacher turnover.

I know that many of you have experience with owning your own businesses. You can imagine the difficulty of keeping things running if you are losing one out of every five of your employees each year. Poor teacher retention has been shown to negatively impact students’ educational achievement and high teacher turnover has been associated with notable drops in the academic performance of students, particularly in (test areas of) reading and math.

While we can’t say for sure why so many of our teachers are leaving their classrooms, we know they are more stressed. According to the 2022 Impact Kentucky working conditions survey, teachers are reporting increased stress for themselves and concern for their colleagues, along with reduced job satisfaction.

Any of you could visit with the teachers in your community to hear from them yourselves about why they are considering leaving or why their peers are.

Shortages in some areas are not new – such as in early childhood, special education, math or science. But we are also seeing a troubling increase in the stress in these areas where there were already shortages.

A critical shortage area is defined as a lack of certified teachers in particular subject areas and/or grade levels using the prior school year’s hiring data. KDE reports these critical shortages to the U.S. Department of Education annually.

From 2018 through the 2021-2022 school year, reported critical shortage areas remained relatively constant at around 42 total areas across the 10 LWAs (local workforce areas). However, for 2022-2023, the number of reported critical shortage areas had a marked increase.

Again, while there have always been shortages in areas such as math, science, special education and highly specialized teaching roles, we are now seeing staffing issues arise in areas such as elementary education and social studies – which historically have had an abundance of applicants. These challenges are particularly tough in rural areas, which accounts for the vast majority of Kentucky’s 171 school districts.

So what are districts doing when the number of openings is increasing – especially in critical shortage areas – but the number of candidates statewide is holding steady.

One effect is that districts are having to be less choosy when it comes to selecting teacher candidates. Some superintendents have told me they feel fortunate to get one applicant for some positions. Districts also are increasingly relying on emergency certifications – which allow people to teach in areas outside of their certification – to fill open positions.

During the 2017-2018 academic year, the Education Professional Standards Board (EPSB) granted 383 one-year emergency certificates. This year, EPSB approved 1,156 emergency certificates – more than a 200% increase.

The EPSB just does not hand emergency certifications out. To be eligible for an emergency certificate, a district must assure that:

- Diligent efforts have been made to recruit a qualified teacher

- No qualified teachers have applied for the position

- The position will be filled by the best qualified person available

While we appreciate those working in these emergency roles, make no mistake – these individuals are less qualified than teachers we have had in the past in these roles. This surge in the need for emergency certifications is a troubling trend for Kentucky and our students.

International and national studies have shown that out-of-field teaching is negatively related to student achievement– particularly in mathematics.

Again, teachers who are teaching out of field can provide a short-term solution to staffing issues, but the effect is that we are hiring more people into teaching roles who are less prepared and qualified than we have in the past. And where these out-of-field teachers are being placed is also a concern.

In addition, the number of students being taught by an out-of-field teacher is not distributed evenly across our students.

During the 2021-2022 school year, which is the most recent data we have, 3.6% of Kentucky’s students attending classes in non Title I schools were being taught by an out-of-field teacher. For students attending Title I schools – which are our schools serving larger numbers of economically disadvantaged students as measured by those qualifying for free or reduced lunch – that number jumps to almost 8%. So not only do these students typically come in further behind and with more challenges, they are also nearly double as likely to have a less qualified teacher working with them.

There are good reasons to be concerned at the state of the teaching profession, but we also should take heed of that maxim often attributed to Winston Churchill, “Never let a good crisis go to waste.” Now is the time for Kentucky to take meaningful steps toward supporting the teaching profession and commit to the long-haul effort it will take for us to restore teaching to the desirable role that we all need it to be.

The reasons for this are complex and long-standing. One issue relates to the total compensation level for educators. After years of erosion of the pay and benefit levels of educators, coupled with an intentional weakening of retirement system incentives to remain in the profession, we should not be surprised that the teacher labor market is presenting us with a shortage. This is a basic and predictable economic result.

A second issue relates to the complexity and demands of the job. As Kentucky has failed to provide funding increases to schools to keep up with inflation, districts must respond by eliminating positions and supports. Yet the need for these roles remain and they fall upon those left working in the building. When schools are de-staffed over a period of years, class-sizes increase and the workload on remaining educators and staff becomes all the more demanding.

And a third reason we are facing teacher shortages relates to the politicization of education over the past few years. As debates over what to do when it comes to COVID-era policies became increasingly partisan, educators were often caught in the middle of intensely personal attacks where there were no solutions that would appease everyone.

As distressing as all of this may be, the origins of the problems also are the potential solutions. At least in my estimation, it all comes down to three main things: pay, support and respect. If we work on increasing total compensation, support for our educators and respect for our educators, I believe we can begin turning the tide on this difficult issue.

I also believe we also have to be clear-eyed about the magnitude of the challenge we face. We didn’t get into this problem overnight and solving it is going to require a focused and multi-year effort if we want to see real results. We have to be wary of quick fixes and small scale solutions which look good on paper, but will not create the magnitude of impact we need to make a dent in this enormous challenge.

In short we need solutions at the scale of the problem.

Leave A Comment