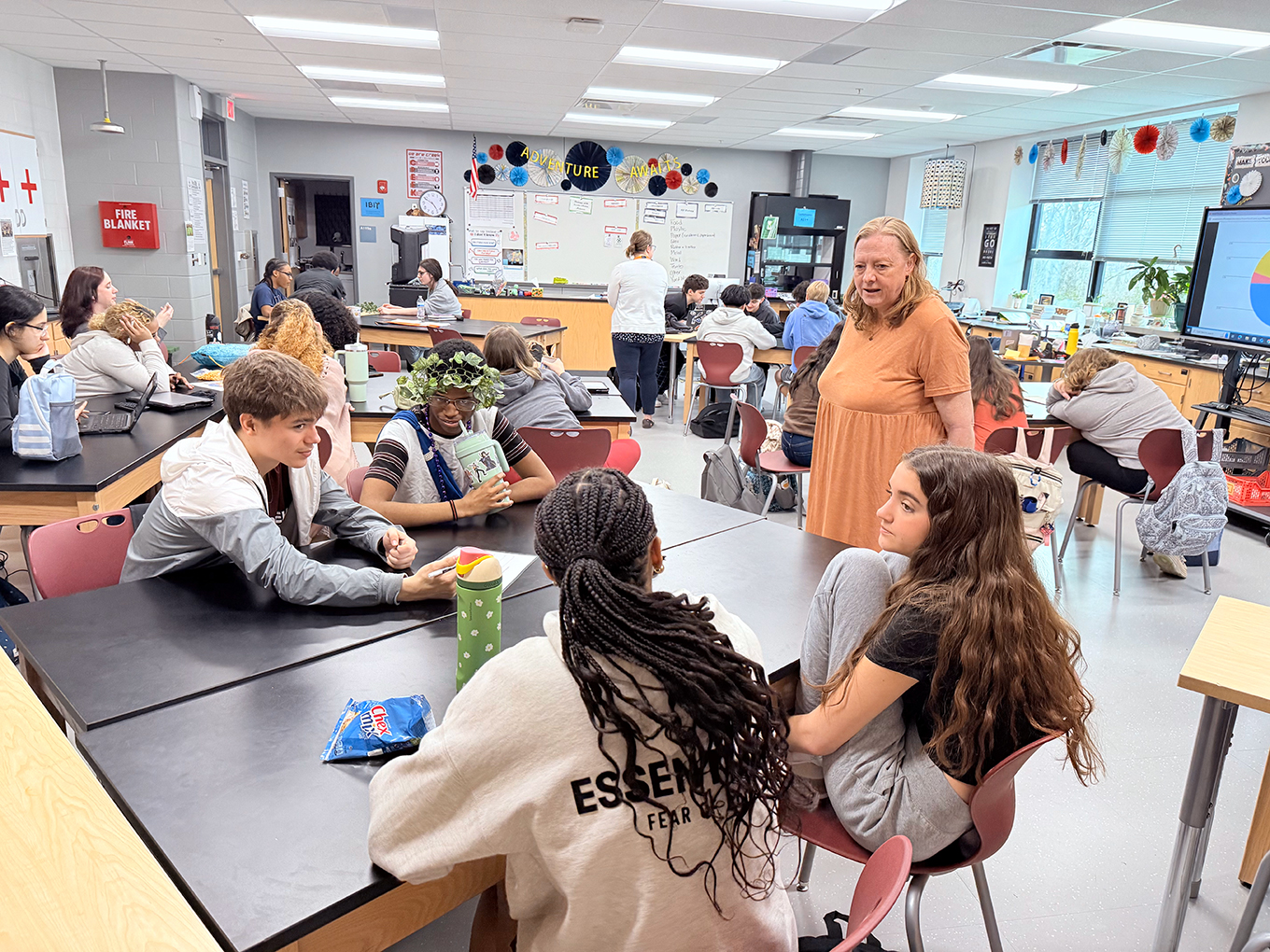

Melanie Callahan uses a puppet theater production of the book “Bear Feels Sick” by Karma Wilson during a creative dramatics class at Laurel County public schools. Callahan, a 4th-grade teacher at London Elementary School and the 2020 Kentucky Elementary School Teacher of the Year, says storytelling can help fill instructional gaps for struggling students or enrich content for gifted students.

Photo submitted by Melanie Callahan

Storytelling is an ancient practice. From cave dwellers to Cub Scout circles, the stories spun around a fire still burn today.

In the age of technology and virtual reality, why is storytelling such an enduring form of communication? The answer lies in how human beings learn and process information, especially during the developmental years. Stories are timeless. Indeed, the theater of storytelling is as compelling as it ever was.

Educational research has revealed that participating in the act of storytelling even can help fill instructional gaps for struggling students or enrich content for gifted students who crave an extra helping of creativity. Students who need extra support can benefit greatly from storytelling that employs techniques such as audio-visual aids and presentations. Storytelling often uses techniques such as music, sound effects, pictures and creative dramatics, which help support learner styles that might fall through the proverbial cracks without thoughtful planning and implementation. As for gifted learners, the rich vocabulary and human elements associated with the art form deepen student understanding of the body of words used in a particular language or culture.

Story designs often resemble real-life plots – usually revealing a beginning, middle and end – which help to foster the understanding of literary structure and sequencing. Legends and fables also serve a greater purpose, whether it is to teach a moral lesson, tell a joke or celebrate a ritual or holiday. Stories have villains and heroes, just like life. Stories share the biographies of human beings from history, social studies and even science.

The magic is not just in the story, but also in the telling. Teachers and librarians have utilized storytelling to link spoken language and instructional content for as long as we can remember. The key to their success has been making a narrative connection between the standard and the story while sharing that creative common ground with kids.

A few years ago, a group of 5th-grade students in my creative and performing arts class were inspired by Washington Irving’s “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” for a storytelling project. The students wrote a script, designed props and costumes, and re-enacted the tale of poor Ichabod Crane and his phantom foe. They used video software and a classroom tablet to document the project, which was later shared in drama class and online. The story came to life with hands-on hard work and technology.

Students in the lower grades responded with great enthusiasm to the work of their peers. The viewers also wanted to “tell stories” and were able to do so with a puppet theater program and similar software. They retold “Snow White,” “Little Red Riding Hood” and “Chicken Little.” Productions were created on their own with a piano, some shiny fabric and hand-crafted puppets. Storytelling was a success from beginning to end.

At its roots, the most successful storytelling starts at home and becomes an educational scaffold. Toddlers learn how to listen as parents and caregivers whisper bedtime stories during those impressionable years of childhood. In preschool, small kids sit in the circle and watch puppets and felt-board characters come to life using their own imagination. Elementary students lean in to their favorite genres and styles. They discover that listening often leads to learning and this trend continues into early adulthood and beyond. This might explain why a variety of corporate retail giants have created audio book apps and websites for folks who crave a story via smartphone. Listening is hip.

According to writer Terry Tempest Williams, “Storytelling is the oldest form of education.” When a storyteller is able to implement dialects and accents, puppets and stick people, or even animated movement, ideas that might have been an abstract concept can turn into a concrete image. In this way, storytelling can help students form a clearer picture in their mind. Storytelling expands visualization. When it comes to concepts such as figurative language or landmark historical events, seeing is often believing.

Many organizations seek to offer the service of storytelling. The Kentucky Humanities Council offers its Chautauqua program for students across the Commonwealth. According to the council, Kentucky Chautauqua has brought to life more than 70 people from Kentucky’s past – both famous and little known. The performers travel to schools and community organizations throughout the state delivering historically accurate dramatizations of Kentuckians who made respected contributions.

As Kentucky teachers, we also have a chance to bring history to life via the local interstate or highway. Storytellers for hire abound on the internet, and I have personally picked up multiple arts grants to bring puppeteers and performers to schools. The productions support learning in everything from reading to history, not to mention the arts and humanities. The human experience is often best-shared via storytelling and calling in professionals can sometimes spark an academic flame that outshines the traditional classroom experience.

I have employed professional and amateur storytellers who share the lives of Benjamin Franklin, Abraham Lincoln and Molly Brown. I have admired 10-feet tall giant puppets who can fill a school gymnasium and hypnotize a kindergarten kid with their height alone. Stories can sometimes raise the roof with their tall tales.

As we approach the spookiest season of the year and autumn leaves litter the ground, this educator encourages teachers of all grades and subjects to give storytelling a shot. Share “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” with a particularly jumpy group of 5th-graders. Describe life aboard “The Beagle” during the dark days of Darwin’s biological research. Use journal logs and diary entries. Pick up a few puppets and perform “Bear Feels Sick” before flu season sets in for real. Try clay animation or stop motion videography to teach technology alongside character, setting and plot.

Finally, get creative with your class and let them tell some tales. Young adults can use any genre of literature to practice public speaking, meanwhile smaller students are eager to step in as authors on almost any topic. Grab an old sheet and a flashlight to share shadow stories. Sit in a circle and form a listening lab. Let the learners take the lead. After all, if you flip your classroom, your students might just flip for storytelling too!

Melanie Callahan is a 4th-grade teacher at London Elementary School (Laurel County). She is a graduate of the University of Kentucky, received her master’s degree from Bellarmine University and Rank I from the University of the Cumberlands. She is an author and illustrator who is studying leadership and family engagement in education through Harvard University’s Extension School. Callahan is the 2020 Kentucky Elementary School Teacher of the Year.

Leave A Comment