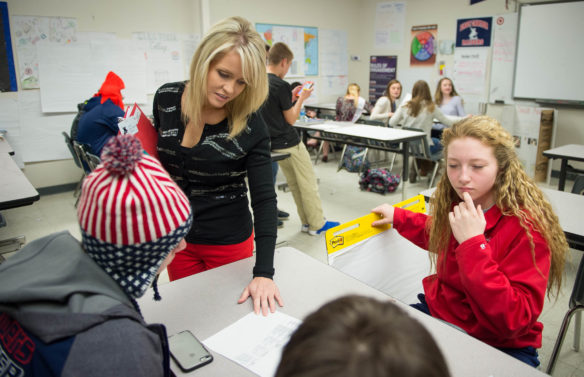

Michelle Ritchie, principal at Perry County Central High School, speaks with students at East Carter High School during a visit. East Carter has been designated a Hub School and serves as a model for school turnaround efforts.

Photo by Bobby Ellis, Feb. 15, 2017

By Brenna R. Kelly

Brenna.Kelly@education.ky.gov

The 10th-graders barely looked up from their Advanced Placement biology work when four visitors came into their East Carter High School classroom and began walking around.

“They are used to it now,” said Sheila Porter, guidance counselor at the 768-student school.

For more than two years, East Carter students have seen Kentucky educators flock to their classrooms to see what the once-struggling school is doing right.

East Carter is one of three schools that once were among the lowest performing in the state, but after assistance from the Kentucky Department of Education, are now among the state’s highest performing. The schools – East Carter, Pulaski County High and Franklin-Simpson High – have been dubbed Hub Schools and now serve as models for school turnaround. Since the program began in 2013, thousands of Kentucky educators have visited the schools to see best practices in action.

The Hub School program is part of Kentucky’s school turnaround effort, which a national group recently hailed as one of the strongest school turnaround models in the nation.

Mass Insight Education, a nonprofit that focuses on school reform, came to that conclusion after performing a diagnostic review of Kentucky’s school improvement work.

“As national experts in school turnaround, we see Kentucky as a national leader in establishing a system of continuous improvement,” Susan Lusi, president and CEO of Mass Insight told the Kentucky Board of Education in February. “We talk about turnaround being dramatic, systemic and sustained, and we believe in many ways, Kentucky has achieved this.”

The report lauded Kentucky for support for low-performing schools, staff levels for school assistance, efforts to close the achievement gap by reducing the number of students who perform at the lowest levels and the Hub Schools program.

“The feedback we received from Mass Insight indicates that Kentucky’s school turnaround process is working,” said Kelly Foster, associate commissioner of KDE’s Office of Continuous Improvement and Support. “This success is the result of the hard work of the Educational Recovery staff and the administrators and teachers at the formerly low-performing schools. It really shows that when everyone is working toward the same goal, improving student achievement, great things can happen.”

When a school is identified a priority school, KDE conducts a diagnostic review to assess the practices that are affecting student performance. KDE then develops 30/60/90-day plans with the school and assigns some of the department’s 58 Education Recovery staff to work with the school to implement the plans.

Of the low-performing schools that have received state support and exited priority status, 74 percent are now performing at a proficient level or above.

That’s the case for the Hub Schools. Franklin-Simpson and Pulaski County were both ranked Distinguished under the state’s accountability system this year, and East Carter was named a School of Distinction.

But six years ago, East Carter’s test scores were in bottom 5 percent in the state. Three years later, after operational and instructional changes, the school had moved up to the 94th percentile in the state.

It took a lot of hard work by the school’s administrators, teachers and KDE Education Recovery staff, said Jeanne Crowe, KDE Education Recovery Leader at East Carter. But they were all committed to the belief that all students could learn at high levels, she said.

“It’s been six years of progress and every year we look at how we can dig deeper,” Crowe said. “We can’t just rest on being a School of Distinction. We have to keep moving forward and looking at what else we can do for our students.”

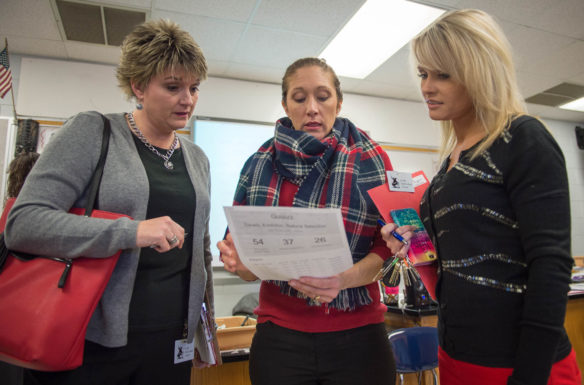

Jaime Tiller, center, a science teacher at East Carter High School, speaks with Dee Amburgey, left, and Michelle Ritchie, of Perry County Central High School, about strategies she uses in her classroom during a hub visit.

Photo by Bobby Ellis, Feb. 15, 2017

And that commitment to continuous improvement keeps educators coming to learn from East Carter and the other Hub Schools. An Education Recovery leader at each Hub School tailors each visit to what the educators want to learn.

“All of our Hub Schools are different,” Crowe said. “It’s not a one size fits all.”

So far this school year, 255 educators from 66 school and 48 districts have visited the Hub Schools to see quality instruction and other best practices in action. Last year, 1,469 educators from 170 schools and 124 districts visited one of the three schools.

For several weeks, East Carter was seeing two visits a week, Crowe said.

“This year we have just about doubled the number of visits from where we were,” Crowe said. “Some weeks we’ve had two visits a week and we’ve had a lot more visits from elementary and middle schools this year.”

Five Perry County Central High School educators recently spent the day at East Carter, where they saw an iLead classroom where students do the teaching, heard from a student panel, learned about reading intervention and dissected student data notebooks.

“We wanted to see everything that could help our school,” Perry County Principal Michelle Ritchie said. “We’re proficient, but we want to go up one more level.

“I could read about what they are doing but it’s different when I actually see it implemented.”

Ritchie was especially thankful to be able to ask Reading Interventionist Marquita Welsh about the program and to witness students teaching biology to their peers in the iLead classroom.

In that class, three students lead each class with teacher Sheri Bonzo watching and guiding from the back of the room.

“I don’t stand up and lecture, this is how they learn,” Bonzo told Ritchie as she observed the class. “It’s a completely different mindset, but it works.”

Ritchie immediately recognized it as something she could take back to Perry County.

“We have students teaching, but not to that level,” Ritchie said. “And when you see it taught to that level, you see how you can implement it and up your program just a little bit.”

In addition to the practices she was planning to see, Ritchie and her team also found ideas about how to motivate students for End of Course exams, how to allow students to fit in both AP and dual credit classes by taking AP classes in 10th grade and options for class scheduling.

All of those practices are the result of a system of continuous improvement that was implemented as part of the school turnaround effort, Crowe said.

“We’ve really tried to make that shift to what is best for kids,” she said. “It’s really a team effort. It’s rewarding for me to be here to see those systems sustaining and see the culture of the school change and the progress East Carter has been able to make.”

MORE INFO …

Jeanne Crowe Jeanne.Crowe@carter.kyschools.us

Shelia Porter Sheila.Porter@Carter.kyschools.us

Michelle Ritchie Michelle.Ritchie@Perry.kyschools.us

Leave A Comment