This article is the last in a series of seven that focus on the core practices of world languages instruction. This series will try to open a window for world languages teachers, nontraditional world languages teachers and other educators as to what world languages education is about. The series will focus on two goals: to grow new leaders in the language learning profession, and to foster growth in students and teachers through effective instructional practices in language teaching.

Read the series:

- World languages: Strengthen your core!

- Core practices: Using the target language as the vehicle and content of learning

- Core practices: Fostering interpersonal communication

- Core practices: Backward design of world language curriculum

- Core practices: Teach grammar as a concept and use it in context

- Core practices: Using authentic texts and resources

By Lea Graner Kennedy

lgraner@stoningtonschools.org

As educators, we know how crucial feedback is for students to make proficiency gains because feedback is both motivating and an important tool to promote learning. For this reason, one of the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL) Core Practices is “Provide feedback in speech and in writing on various learning tasks.”

Questions often arise regarding the types and the frequency of feedback that students need to gain proficiency. This article focuses on providing insights and strategies that answer both questions, because feedback is an area where we can all work smarter – not harder – to deliver improved learner performance.

- The first and most important aspect of feedback is to focus on the student’s zone of proximal development (ZPD).

Channeling the work of the famous developmental psychologist Lev Vygotsky has been one of the most important lessons that I have learned with regards to feedback. In a nutshell, Vygotsky’s ZPD tells teachers only to give learner feedback that will bring students up to the next level. Challenge the learner to promote growth, but not be too difficult for the learner to absorb.

As language teachers, we often forget the small steps we took on our own proficiency journeys and feel the need to give more feedback in speech and in writing than the learners can possibly utilize. This tendency gives us more work, with little or no student gains. In fact, overloading the learner with feedback that is too far beyond their actual level, not within their zone of potential growth or ZPD, is demotivating for students. Limiting our feedback to that which is in their zone is a double win; less work for the teacher and more comprehensible input for the student.

When teachers hear errors in speech, it is important resist the temptation to give students more feedback than they can process. Errors are a critical part of creating with language and moving through the intermediate level of proficiency.

For language teachers, perhaps it is better to think of an area where we ourselves are trying to learn a new skill, such as athletics or music. It is only when we think about an area where we view ourselves as a novice or intermediate that we become clear on the strategies we need as learners to progress.

There are several documents and rubrics that make providing feedback easier to deliver to students because they provide a common language to use in discussions about how to move up the proficiency scale, such as the Can-Do Statements, AAPPL rubrics or Feedback Rubrics from Level Up Language. These tools help students and teachers to become mindful of their actual proficiency level and set goals based on their potential growth level.

Once we begin to internalize the lessons of Vygotsky, we give only the feedback that will help students improve their output. The ACTFL’s Assessment of Performance toward Proficiency in Languages (AAPPL) and Level Up Language rubrics are particularly helpful in giving efficient ways to provide feedback to students because the strategies are clear and specific to promote growth. Students can use the rubrics for self-assessment and for peer-assessment as well, because they provide an easy way to highlight measurable strategies needed for growth.

- When considering feedback, we must consider both the variety of feedback we give to our students and the role the teacher plays in giving feedback within the classroom setting.

When the teacher is a facilitator, students have more opportunities to use the language for authentic purposes in all three modes – presentational, interpretive and the interpersonal. In “Enacting the Work of Language Instruction: High Leverage Teaching Practices” by Eileen Glisan and Rick Donato, the research behind each of the current Core Practices is explained clearly for teachers. They share the importance of teachers creating a “discourse community,” which is an interactional space where students have opportunities to negotiate meaning in authentic ways.

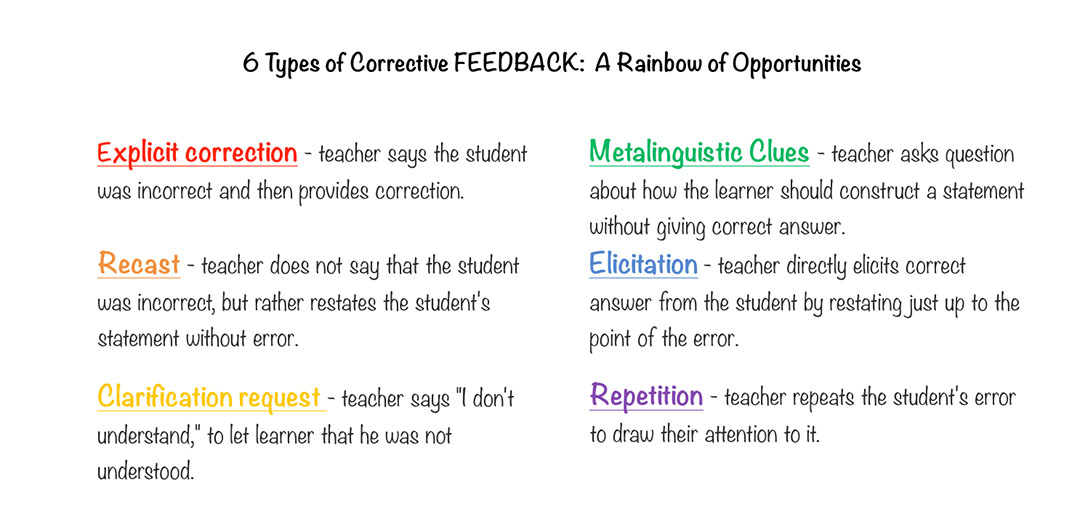

In this interactional space, teachers will need to consider how to vary their oral feedback to improve performance. There are six types of corrective feedback that we need to have in our toolbox: explicit correction, recasts, clarification requests, metalinguistic feedback, elicitation and Repetition.

Knowing that we have a choice of options to provide our students is extremely powerful. This is a brief description of the types:

Submitted by Lea Graner Kennedy, adapted from Diane J. Tedick and Barbara de Gortari

All corrective feedback is used to prompt the learner to notice the error and try to fix it. The research about how to vary the use of these types of feedback is important if we are looking at uptake, the ability for the student to process the learning and self-correct.

In the book by Glisan and Donato, research shows that teachers use recast 55 percent of the time – more than the other types of feedback – however, it is the least effective. By contrast, the most effective corrective feedback leading to student uptake is elicitation. This research prompts teachers to become cognizant of the types of feedback they are providing to students.

Their book illustrates the importance of teachers tapping the wide range of opportunities to promote uptake and being mindful about varying our types of feedback. For students to internalize the feedback we provide for them, they need to receive varied feedback that is within their potential learning area.

Our goal as language teachers is to motivate students to make gains in proficiency. To that end, we should remember errors are critical to their growth and that our focus on perfectionism can stunt their progress. We want the students to commit to risk-taking and be open to elaborating in the target language, while also encouraging reflection on feedback received.

As Elon Musk said in an interview with Mashable, “It’s very important to have a feedback loop, where you’re constantly thinking about what you’ve done and how you could be doing it better. I think that’s the single best piece of advice: constantly think about how you could be doing things better and questioning yourself.”

Building a discourse community, with ample opportunities for input and timely feedback on output, is crucial to creating the feedback loop.

We are the experts in the language arena. But when we step into a different arena, such as learning a new instrument or a sport, we then become much more empathetic to the needs of giving feedback within the zone of proximal development and of providing plenty of opportunities for students to receive comprehensible input before asking them to provide output. It would be like us taking voice lessons with Beyoncé and getting feedback on how to win a Grammy when we are mere novice high students.

As we step back in the language arena this year, we can move our novice students forward by providing appropriate feedback and establishing a discourse community. By guiding our learners to reach the desired learning targets with timely and varied feedback, based on their current proficiency level, we can help them to advance on their path to proficiency.

Lea Graner Kennedy is the world language coordinator for Stonington Public Schools in Stonington, Conn., where she teaches both French and Spanish She is regional representative for the Northeast Conference on the Teaching of Foreign Languages, board member for the National Association of District Supervisors of Foreign Languages, and president-elect of the Connecticut Council Of Language Teachers. Kennedy has been in the education field for 24 years, serving as a classroom teacher, coordinator for foreign languages and world language consultant. She was named Supervisor of the Year in 2016 by the National Association of District Supervisors of Foreign Languages.

Leave A Comment